Circe, Odysseus and the Disclosure of Hermes

Published by Reblogs - Credits in Posts,

Stephen Pimentel

The Circe Narrative

In Greek mythology, Circe is a goddess, though not one of the Olympians. Rather, she seems to represent an older stratum of religious practice and belief in the Mediterranean. She is the daughter of Helios, god of the sun. Circe is described as polupharmakos (Od. 10.276), one who works with "many drugs", in the sense of a worker of plant medicines. The use of plant-based substances both as medicines and poisons in the Bronze Age Mediterranean was not scientific in either the Classical or modern senses, but fundamentally shamanic in character.

Shamanism is a set of spiritual practices in which a shaman, a figure believed by a community to have an ability to interact with spirits, enters states of altered consciousness through rituals to perform works such as transformation into a totem animal, healing, or divination. Chanting and the use of plant-based psychoactive drugs are often employed to facilitate these states and establish connection with spirits. Circe might perhaps best be understood as a shamanic figure, representing inherited cultural forms in confrontation with something new.

Circe, Wright Barker, c.1889 (Cartwright Hall Art Gallery, Bradford, UK).

Circe’s encounter with Odysseus is described in Odyssey 10.140–574, during Odysseus’ extended account of his wanderings to the Phaeacians (Books 9–12). The setting of the scene initially seems straightforward: Odysseus arrives with his ship and exhausted crew on the island of Aeaea; climbing to a high point, he sees the smoke from a fire rising in the middle of the island (10.148–9). The next morning, after everyone has feasted and rested, he divides his men into two groups, puts one of the groups under the command of his brother-in-law Eurylochus, and draws lots to see which of them will go to explore the source of the fire. The lot falls to Eurylochus, who proceeds with his group into the forest to investigate.

Homer’s narrative construction in this section is subtle and should be read with care. He maintains close control over information, with respect to who conveys what data, as well as the manner in which each bit of information is conveyed. It is crucial to note that, within the narrative, Odysseus does not witness what happens to Eurylochus’ group. Rather, Odysseus simply recounts what Eurylochus later told him when he returned. Eurylochus was alone and almost incoherent, "stunned by the great sorrow, and both eyes filled with tears," able to "think of nothing but lamentation" (10.247–8). Eurylochus himself did not fully witness what happened after his men went into Circe’s house: he was too suspicious or afraid to accept Circe’s invitation and enter her house with the rest of his group (10.232, 258). He only listened to what happened from outside and guessed the course of events from what he could hear.

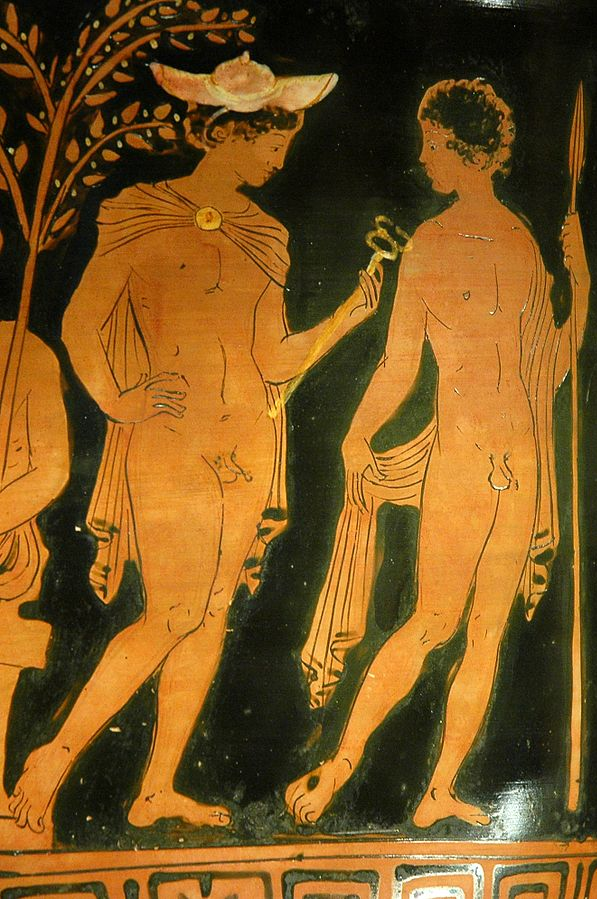

Odysseus between Eurylochus and Perimedes as he consults the ghost of Tiresias: detail of a Lucanian krater, c. 380 BC (Cabinet de Medailles, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris).

The men in Eurylochus’ group are still in shock from the massacres they have survived. They soon come to a house made of "stones, well polished," around which roam wolves and lions that are strangely friendly, like dogs greeting their master (10.211–16). They assume that these uncanny beasts have been enchanted, and their fear redoubles (10.219). The men are immediately drawn by the sound of a woman "singing in a sweet voice" as she weaves at a great loom (histon) (10.221–8). The singing induces a euphoria in all the warriors but Eurylochus; they swiftly forget their fear and call out to the woman (10.229). One could interpret Circe’s singing merely as welcome emotional relief from a tense situation, but particular forms of singing or chanting are a standard part of shamanic practice to facilitate altered states of consciousness. Indeed, the etymology of the English "enchant" (from the Latin incantare) reflects analogous practices.

When the men call, Circe comes and invites them into the house. All enter except Eurylochus, who fears a trap (10.230–2). Circe gives the men a mixture of "barley and cheese and pale honey added to Pramneian wine" (10.234–5) into which, unknown to them, she has mixed "malignant drugs, to make them entirely forget the land of their fathers" (10.235–6). After they have ingested the drugs, she strikes the men with her rod (rhabdos) and pens them in her sties, where they have "the look of pigs", although "the minds (nous) within them stayed as they had been before" (10.240–1).

Circe and the friends of Ulysses (Odysseus), Briton Rivière, 1871 (priv. coll.).

The perception that men have assumed the form of animals through the use of ritual and drugs is a common feature of shamanic practice, whether such a phenomenon is perceived by the shaman himself or by those on whom he acts. The animals whose forms are assumed are chosen, not at random, but for their symbolic place within mytho-religious belief. They are almost always predators. In early Indo-European war-bands, the animal that men were said to become was the wolf. In later Nordic practice, attested through the 1st millennium AD, it was the bear.

Against this background, there is a stark symbolism in Circe’s choice of the pig. As distinct from the wild boar, the pig is not a predator. On the contrary, it is an emblematically domestic animal. Pigs formed an integral part of early agriculture and, according to at least one convincing study, "formed a key component of the Neolithic Revolution" in the 9th millennium BC, reaching Europe from the Near East by the 4th millennium BC. By inducing Odysseus’ men to assume the form of pigs, Circe has made them forget their identity as warriors, and thus cast them into an agricultural frame, domesticating them against their wills and penning them in.

Circe (labelled "Kirka") offers a basket to Odysseus, who stands in front of her loom: Boeotian black-figure skyphos, 450–420 BC (British Museum, London).

A sympathetic reader might view Circe’s response, however severe, as more defensive than aggressive: she lives in isolation with only a few maidservants, and a Mycenaean warrior band has come unannounced to her home. It is perhaps understandable if she instantly decides to deal with the threat.

Upon hearing Eurylochus’ tale, Odysseus immediately decides to go to Circe’s house and rescue his men. He sets off alone; Eurylochus begs not to be taken back (10.261–9). As Odysseus approaches Circe’s house, he is stopped by the god Hermes (10.276–8), who warns him that, without assistance, he will not only fail to escape from Circe, but will also share the fate of his men (10.281–5). To help Odysseus avoid that fate, Hermes offers him a "good drug" (10.287) that he must take before going to Circe’s house, so as to thwart her use of bad drugs (10.287–8).

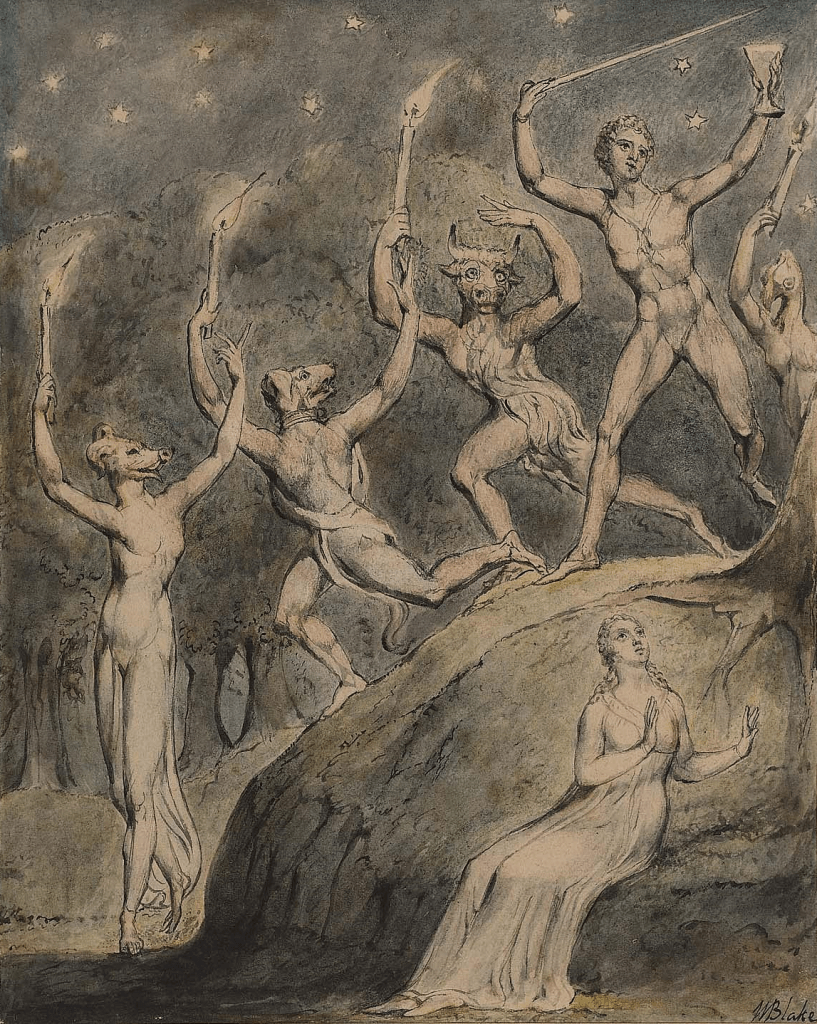

According to John Milton in his 1634 masque Comus, Comus was the son of Circe by Bacchus, and also transformed strangers into beasts that "roll with pleasure in a sensual sty": Comus with his Revellers, William Blake’s illustration to Milton’s Comus, c.1815 (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA).

Hermes then describes in more detail "all the malevolent guiles of Circe" and how Odysseus may overcome them (10.289). Circe’s chief technique is to "put drugs in the food, but she will not be able to enchant (thelxai) you, for this good drug which I give you now will prevent her" (10.291). Odysseus relates that Hermes picked the plant "out of the ground, and he explained the nature (phusis) of it to me. It was black at the root, but with a milky flower. The gods call it moly. It is hard for mortal men to dig up," but not for the gods (10.303–6).

Having taken this antidote to Circe’s drugs, Odysseus approaches her house. He sees no wolves or lions roaming around the house, as Eurylochus reported. Circe invites him into the house and serves him her drugged mixture (kukeōn). She attempts to do to him what she did to his men, striking him with her rod and commanding him to go to the pig pen, but this time it has no effect. She cries out in astonishment: "The wonder is on me that you drank my drugs and have not been enchanted, for no other man beside could have stood up under my drugs, once he drank and they passed the barrier of his teeth. There is a mind (noos) in your breast that is proof against enchantment" (10.326–9).. She recognizes him as Odysseus, of whom Hermes had long ago warned her (10.330–1).

Circe, Frederick Stuart Church, 1910 (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA).

Shamanic Transformation

Homer gives us two distinct descriptions of the enchantment of Odysseus’ men – one from Eurylochus (10.239–40) and one from Circe (10.329) – and they contradict each other. According to Eurylochus, the men’s bodies were changed, but their minds remained the same. According to Circe, it was Odysseus’ mind that was proof against deception, implying that it was the mind on which her drugs acted. Circe’s explanation is quite consistent with the interpretation that the men ingested a powerful hallucinogen that induced a subjective experience of transformation. Hermes’ drug, in turn, acted for Odysseus as an antidote to the hallucinogen.

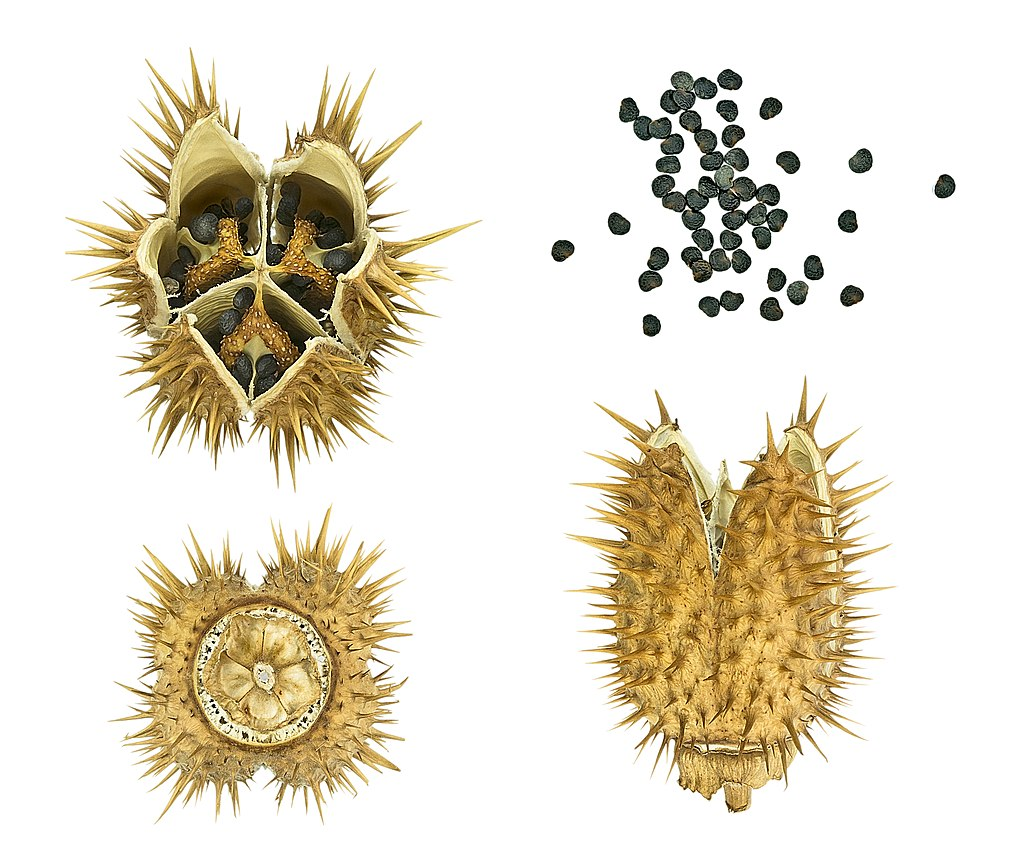

It may be difficult for modern readers to imagine a drug under whose influence a group of men might become convinced that they had been transformed into beasts. We have some cultural familiarity with classical psychedelics (mostly substituted tryptamines such as psilocybin, DMT, or LSD); yet even at their higher doses such an effect would be unusual. Are there any plants likely to have been used in the Bronze Age Mediterranean that could have had such an effect? Indeed, there are several candidates.

The Solanaceae family of plants is now familiar to us from New World cultivars, including the tomato, potato, and bell pepper. However, it also includes members (such as mandrake, henbane, and deadly nightshade) that contain tropane alkaloids – anticholinergic agents that are not only potent hallucinogens, but also deliriants. They produce "extreme mental confusion, strong and realistic hallucinations," often with "a feeling of alteration of the skin, as if growing fur or feathers." Such Solanaceae are found throughout the Mediterranean. In fact, we have direct archeological evidence of the use of Solanaceae in a shamanic context during the Bronze Age. This evidence was obtained from analyzing human remains on the Mediterranean island of Menorca. The remains were found with a figurine representing the transformation of a man into a beast.

Jimsonweed (datura stramonium).

An episode from early American history may illustrate the effect and potency of tropane alkaloids from Solanaceae plants. In 1676, a group of British soldiers was sent to the Jamestown colony in Virginia in response to Bacon’s Rebellion, an armed revolt against the colonial governor that was led by Nathaniel Bacon (1647–76). The soldiers were unfamiliar with the local flora, and gathered some quantity of an edible-seeming plant that they hoped to use in a salad. The plant turned out to be Datura stramonium, later known as Jamestown weed or jimsonweed, a Solanacean plant common in the New World and rich in tropane alkaloids. After consuming the salad, the soldiers began spontaneously acting like beasts. The colonists had to confine the drugged soldiers for several days "lest they should in their folly destroy themselves".

The burning of Jamestown, VA, during Bacon’s Rebellion (1676/7): illustration by Howard Pyle for the article "Jamestown" in Harper’s Encyclopaedia of United States History, from 458 AD to 1901 (Harper & Bros., New York, 1901).

As for moly, the "good drug" that Hermes shows to Odysseus, a very probable candidate is snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis), which is found throughout the Northern Mediterranean. Snowdrop contains galantamine, a centrally acting anticholinesterase, i.e., an agent that blocks or reverses anticholinergic intoxication. The use of moly in the Odyssey would then be the oldest recorded medicinal use of such an agent for this purpose.

The common snowdrop (galanthus nivalis).

The Root of Philosophy

Hermes’ intervention with Odysseus is notable in that the Olympian invokes no transformative power of his own, as one might expect of a god; rather he simply explains to Odysseus certain truths about the world. In particular, Hermes "explained (edeixe) the nature" of the moly (10.303). The verb deiknumi means "to show", but also "to give instruction". The phusis of moly, which yields its capacity to function as an antidote to Circe’s drugs, is not evident simply by looking at the plant; it must be explained. As a result of Hermes’ explanation, Odysseus acquires new knowledge and, through that knowledge, a new power.

Implicit in Hermes’ disclosure of the nature of moly is the fact that things in general have natures. A great many plants served as drugs in the ancient world. Neither moly nor the plants used by Circe were unique in this regard. That the nature of a thing governs its functions is true of every living thing that we encounter. According to the Classicist Seth Benardete (1930–2001), this disclosure is the very "peak of the Odyssey".

Mercury (Hermes) protecting Ulysses (Odysseus) from Circe’s charms, Ruggiero de Ruggieri, 1569 (Château de Fontainebleau, France).

What are these "natures" that Hermes’ disclosure of them should have such importance for the Odyssey and beyond? An initial clue is that Hermes does not create the moly plant himself; he does not produce it with a wave of the caduceus. The plant is no artifact: it grows in the earth of its own accord; this fact of growth is essential to what is being disclosed. Although phusis is customarily translated as "nature", it more literally means "growth".

The noun phusis is formed from the verb phuō, meaning to "grow", "beget", or "give birth to". It refers not so much to the process of growth as its result – the realization of some organic process. Hermes’ explanation of a particular phusis – how moly, when ingested, acts in relation to other drugs – already suggests the more general character of phusis as the principle from which the essential properties of a living thing come.

The philosopher Heraclitus, who was active in the late 6th century BC, adopted phusis as the basis of his reflections. He declares in one famous fragment that, what Hermes did for moly, he will do for the many things of the world, "distinguishing each thing according to its phusis and explaining how it is" (fr. 1). In the Odyssey, Hermes describes moly, rooted in the earth, as: "hard for mortal men to dig up" (10.305–6). If the moly root serves as a synecdoche for the phusis of living things, then it is precisely knowledge of natures that is difficult, though not impossible, for man to acquire. Phusis lies hidden in relation to man, like the root of a plant beneath the earth. As Heraclitus notes, "phusis loves to hide" (fr. 123).

Heraclitus (detail), Peter Paul Rubens (school of), c. 1637 (Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain).

The effort required to attain knowledge of natures is an initial source of difficulty: the moly revealed by Hermes "was black at the root, but with a milky flower" (10.304), suggesting that the beauty of the white flower so captivates the attention that the unattractive black root is ignored: man has a tendency to attend to the surface of things, not applying his intellect to what the eye does not see.

A deeper source of difficulty is the fact that natures are not of human making. Phusis is not nomos – it is not, to use a modern term, a social construct. It is fitting that phusis is disclosed by Hermes, the crosser of boundaries: to learn of phusis, man must pass, in thought if not in body, beyond the polis, the environment built by and for man, to that ancient, indeed primordial, sphere that precedes all man-made environments. Precisely because phusis is not made by man, it is beyond his immediate grasp and can only be disclosed to (or discovered by) him.

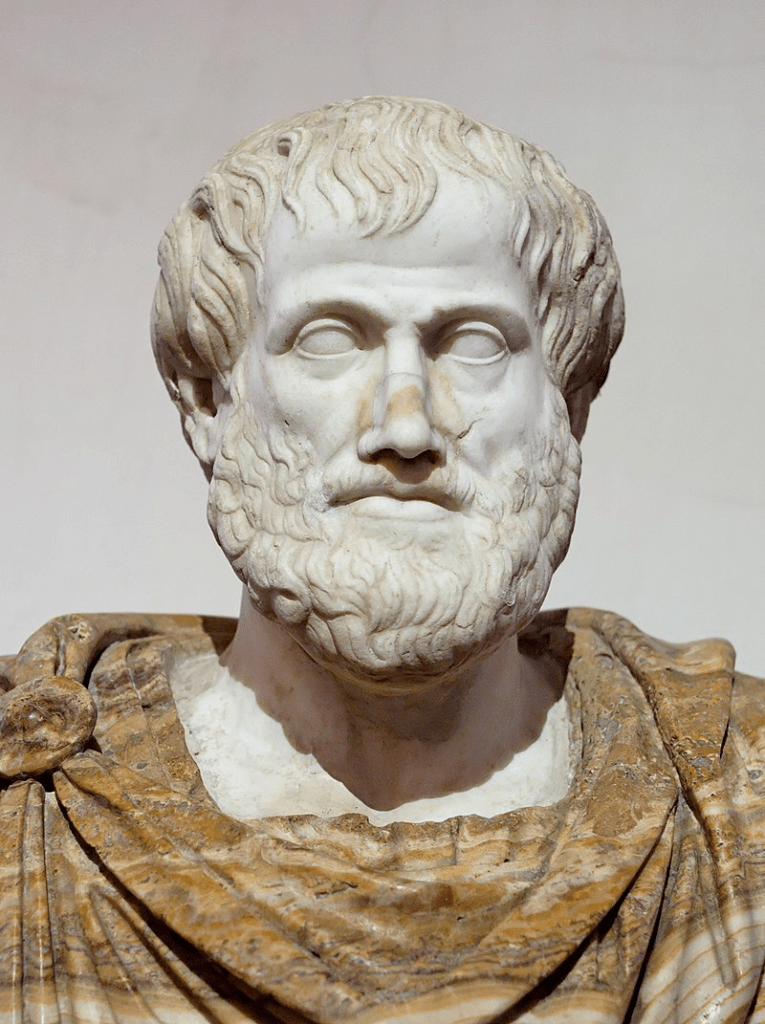

Bust of Aristotle, Roman copy after a Greek bronze original by Lysippus of 330 BC (National Roman Museum, Palazzo Altemps, Rome, Italy).

The seed that Homer planted blossoms in Aristotle. In his Physics, Aristotle describes phusis as the internal source of the dynamic properties of things such as animals or plants, as distinct from things that man produces by art. The means by which we come to know the phusis of a thing, according to Aristotle, is precisely that which Hermes showed to Odysseus, by "coming face-to-face with" (epagōgē) the thing in the contemplative intellect (nous), the very faculty that in Odysseus was "not to be enchanted". And yet phusis is not a product of the mind, but a result of the activity internal to the thing itself – the activity that makes it the kind of thing it is.

Ever the biologist, Aristotle observes a biosphere in which living things, however vast in their variety, consistently reproduce, in accord with their kinds, while living in ordered ecosystems that supply their needs. They come into the world and grow, guided by their phusis, until they have obtained the properties fit for them. However sophisticated and technical Aristotle’s discussion becomes, phusis always retains a sense of "growth" in his work and therefore echoes – even if at a distance – the disclosure of Hermes.

Hermes and a young warrior: detail of Side A of a red-figure krater by the Bendis Painter, 380–370 BC (Musée du Louvre Museum, Paris, France).

The Olympian Difference

Homer contrasts Hermes and Circe in regard to how they relate to the world. Hermes is an Olympian god, in contrast to the older deities whom the Olympians displaced. His stance toward Circe is detached: he does not interact directly with her in the episode, but only with the mortal Odysseus, and only to confer knowledge upon him. Hermes’ immediate goal is to give Odysseus an understanding of Circe’s methods and a precise means to counteract them, but in doing so he also conveys the knowledge that things have natures.

Did Circe have the same knowledge of natures as Hermes? Perhaps, but the exact state of her knowledge within Homer’s narrative is less important than the shamanic background within which she works. Shamanic lore is often effective because it relies on the phenomenology of the effects that things have on humans – including psychosomatic effects. Nevertheless, while the shamanic use of drugs relies on their natures, it does so unwittingly. It entails neither a knowledge of natures nor even a conception of them. Instead, it holds that spirits are associated with, but separable from, things and seeks to influence humans through those spirits. There is a conceptual step it has not yet taken: to grasp that natures inhere in things, which is a prerequisite to working to deepen one’s knowledge of those natures. Aristotle will call the latter epistēmē and explain it as "knowledge through causes".

Penelope weeping over the bow of Ulysses, Angelica Kauffmann, 1779 (William Benton Museum of Art, Storrs, CT, USA).

Homer has presented Odysseus as a man whose mind can grasp the nature of things, and so the forerunner of a philosopher. Hermes shows Odysseus that things have natures, and that those natures, like the drugs of Aeaea, can be beneficial as well as harmful. The critical implication is that natures are themselves real: they govern the properties of living things and the ways in which they interact; they point beyond the appearance of things to their depths. With the knowledge of natures, Odysseus receives a power of action that he would not otherwise have.

As a king and leader, Odysseus has a strong desire to rescue his men from captivity. He is so unhesitating that he nearly rushes into Circe’s trap. It is Hermes’ disclosure of the knowledge of particular natures that allows him to take the antidote to her poison and, as Circe exclaims, protect his mind from deception. Only then is he able to act for the good of his friends in a way that is properly political.

Without a knowledge of natures – and especially, as Socrates would emphasize, the nature of man – man can be enchanted, politically and otherwise. Man can then easily fall back into shamanism, although in modernity it tends to be concealed under the name of ‘progress’. And if a society should expressly deny the reality of natures, who can know the transformations of the human to which it might become vulnerable?

Stephen Pimentel is an essayist and reader of the Classics and political philosophy. He works in technology in the San Francisco Bay Area.