Homer in the Byzantine Classroom

Published by Reblogs - Credits in Posts,

Fully:

"Homer in the Byzantine Classroom - Eustathios of Thessaloniki and John Tzetzes"

by Baukje van den Berg

In the year 1204, crusaders from the Latin West besieged and sacked Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. Whereas the western half of the Roman Empire had fallen apart towards the end of the 5th century AD, its eastern half continued to exist until 1453, with Constantinople as its capital, Greek as its principal language, and Orthodox Christianity as its official religion. This Eastern Roman Empire is now often referred to as the Byzantine Empire, a modern name that was not used during the Middle Ages. Political tensions between the Byzantines and the crusaders had led the latter to capture the city, although they had actually been on their way to Egypt and the Holy Land to defeat the sultanate of the Ayyubids and reconquer Jerusalem from the Muslim ‘infidels’.

The Sack of Constantinople in 1204, as illustrated in a 15th-century manuscript commissioned by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, France: Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal MS-5090 réserve f.205r).

The capture of Constantinople was accompanied by plundering and destruction. A Byzantine historian and eyewitness to the events, Niketas Choniates (c.1155–1216), disapprovingly describes how the crusaders, in dire need of money, melted many of the bronze statues in Constantinople to mint coins. These included ancient statues of Hera, Heracles, and Helen of Troy, whom Choniates addresses with pathos:

O Helen, Tyndareus’ daughter… where are your irresistible love charms? Why did you not make use of these now as you did long ago … It was said that these sons of Aeneas condemned you to the flames as retribution for Troy’s having been laid waste by the firebrand because of your scandalous amours. (History 652; trans. after Magoulias 1984)

Choniates disagrees: the crusaders’ greed, not their erudition or sense of history, brought them to melt the statues of Helen and others. For him, the crusaders’ actions prove that they are unable to appreciate ancient art and understand the cultural significance of Helen, whose fame is inextricably connected to Homer and the great authority of his Iliad, a foundational text in Byzantine culture. The crusaders did not know their Homer and so did not share this cultural knowledge; Choniates therefore calls them barbarians, from whom you could only expect such savagery.

Niketas Choniates, as depicted in a 14th-century manuscript of his Chronicles (Austrian National Library, Vienna, MS Cod. Hist. gr. 53*, fol.1v).

Homer after Antiquity

Choniates’ indignation over the destroyed statues illustrates how deeply the heritage of Ancient Greece was rooted in the cultural identity of the Byzantines or, more specifically, of the educated Byzantine elite. Since antiquity, Homer had been considered the founder of Greek culture and literature. His poetry held a central position in the school curriculum: young students learned to read and write by studying the Iliad and (to a lesser extent) the Odyssey. When, in the 4th century AD, Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire, an education steeped in Ancient Greek literature continued to be valued by the elite.

Until the final conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans in 1453, Homeric poetry kept its vital role in Byzantine education and literary culture. Every educated person was expected to possess a profound knowledge of ancient literature. Byzantine schoolboys therefore continued to study Homeric poetry during their grammatical and rhetorical schooling. How did this work in practice? In this article, we will visit the classroom of two teachers active in Constantinople during the 12th century, a period of great cultural flourishing and prolific literary production.

Idealised portrait of Homer by an unknown Flemish artist, 1639 (Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD, USA).

John Tzetzes

Much of the educational provision in Byzantine Constantinople was in the hands of private teachers such as the grammarian John Tzetzes (c.1110–80). We know about Tzetzes’ biography only from what little information he provides in his own works: he was probably born around 1110, received a strict education from his father, and strove to make a living as a ‘freelance’ writer and teacher. As a grammarian, he instructed his students in Ancient Greek language and literature, often to prepare them for a career in ecclesiastical or imperial administration.

Next to his teaching activity, Tzetzes produced literary works for aristocratic patrons, whose financial support was in high demand during this period. Throughout his oeuvre, Tzetzes repeatedly complains about poverty and a lack of appreciation for his talents. Even if we should take such complaints with a grain of salt, he indeed never seems to have penetrated to the highest intellectual circles of the capital, to which Eustathios, our second teacher, belonged. If we are to believe Tzetzes, he always remained an outsider, who had to work hard to recruit students and land literary commissions.

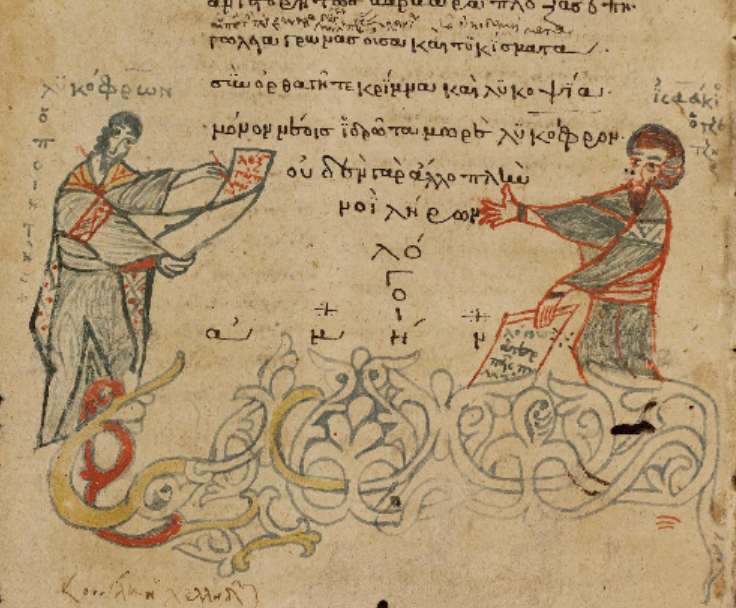

A 13th-century illumination in the commentary on Lycophron’s Alexandria that John Tzetzes compiled with his brother Isaac: here Isaac seems energetically to explain the poem to the poet himself (University Library, Heidelberg, Germany, MS Cod. Pal. graec. 18 f.96v).

Tzetzes produced many didactic and scholarly works on ancient literature, including exegetical works on Homeric poetry of various kinds and for different audiences. They therefore illustrate well the different ways in which Homer was taught in this period. Tzetzes’ first Homeric work was the Little Big Iliad (Mikromegalē Ilias), a poem of some 1,700 hexameters narrating the entire history of the Trojan War, from Hecabe’s ominous dream anticipating the birth of Paris to the capture of the city.

The poem summarizes in three parts the events preceding the Iliad (Antehomerica), the course of the Iliad itself (Homerica), and the developments after Hector’s death (Posthomerica). Tzetzes furnished his text with explanatory notes or scholia, which demonstrate how he used it in his teaching practice. Many of these notes are of a grammatical nature and explain, for instance, the meaning of Homeric words or the rules of Ancient Greek morphology.

Illustration of the capture of Dolon from the "Ambrosian Iliad", produced in the 5th cent. AD (Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan, Italy Cod. F. 205 Inf., f.34).

The scholia also provide a great deal of background information on issues such as the genealogy of heroes or other historical facts in the text. Grammarians thus instructed their students not only in linguistic competence but also in cultural knowledge – that is to say, the kind of knowledge that every educated person in Byzantium was expected to have. The Little Big Iliad, however, is more than a didactic work: it is an autonomous piece of poetry showcasing Tzetzes’ erudition and literary virtuosity. It was a technical challenge to write in the ancient meters, all the more so because the spoken Greek of the 12th century no longer distinguished between long and short vowels, as Ancient Greek routinely did. The poem might therefore also have served as a set piece, as a carte de visite of a teacher and writer in search of students and commissions.

Different in tone and approach are the Allegories of the Iliad and Allegories of the Odyssey, written in accentual fifteen-syllable verses. Tzetzes undertook this project initially at the behest of Empress Irene, the spouse of Emperor Manuel I Komnenos (r.1143–80). As a foreign princess from Bavaria, Irene needed a crash course in Homer to be able to participate in Constantinopolitan court culture. For every book of the Iliad and the Odyssey, Tzetzes first gives a brief summary of the plot, followed by an allegorical interpretation. He mostly explains the Homeric gods as natural elements or as planets and stars, as ancient exegetes had done before him. He was convinced that Homer did not really believe in the pagan gods, but had meant for his mythical tales to be read on a deeper level. With his allegorical reading, Tzetzes thus aimed to reveal the true meaning of the Homeric epics, as intended by the poet himself.

A Roman bust of Homer, 2nd cent. AD, copying a lost Hellenistic original (British Museum, London).

Let us look at a passage from the Allegories of the Iliad by way of illustration. In the poem’s third book, Menelaus and Paris (aka Alexandros) meet in a duel, which is about to end badly for Paris before Aphrodite appears and removes him from the battlefield. Tzetzes first summarizes the scene and then gives his allegorical reading:

And Menelaus would have killed him right there,

had not Aphrodite saved him then

by cutting his helmet strap,

and whisking him away to his bedchamber

and laying him down next to Helen.

Learn now the allegory of Aphrodite.

Those born under Venus,

when it lies in good position, are saved from dangers.

As this was Alexandros’ birth star,

thus he escaped, being saved when the strap was cut.

Because she also makes desirable those born under her sign,

Helen, despite having greatly struggled with herself,

was seduced by his beauty, even after such a defeat,

and thus she lay with him as if he had won. (Allegories of the Iliad 3.158–71, trans. Goldwyn and Kokkini 2015)

Helen causes Menelaus to drop his sword, as Eros and Aphrodite look on (red-figure crater by the ‘Menelaus Painter’, Athens, 440s BC; now in the Musée du Louvre, Paris, France).

Tzetzes here explains Aphrodite’s intervention from an astrological perspective: she is no anthropomorphic goddess who physically appears on the battlefield to save her protégé. What Homer means is that Paris was born under the planet Venus. This planet protects him from danger and makes him so irresistible that Helen sleeps with him – even despite his disappointing martial achievements.

Tzetzes discusses his ideas about the correct interpretation of Homeric poetry more elaborately in his most scholarly work, the Exegesis of the Iliad, written in prose. In the long prefatory essay, he presents his work as the first commentary ever to address all aspects of the entire Iliad – no-one past or present has ever undertaken such an ambitious project, Tzetzes stresses in his characteristically confident tone. However, he never seems to have completed the Exegesis: apart from the preface, we have scholia only on the poem’s first book. The commentary offers a wide variety of explanations, addressing issues of grammar, rhetoric, and meter as well as mythology and ancient history. In its nature and (planned) extent, the work therefore resembles most closely the Homeric project of our second teacher and scholar, Eustathios of Thessaloniki.

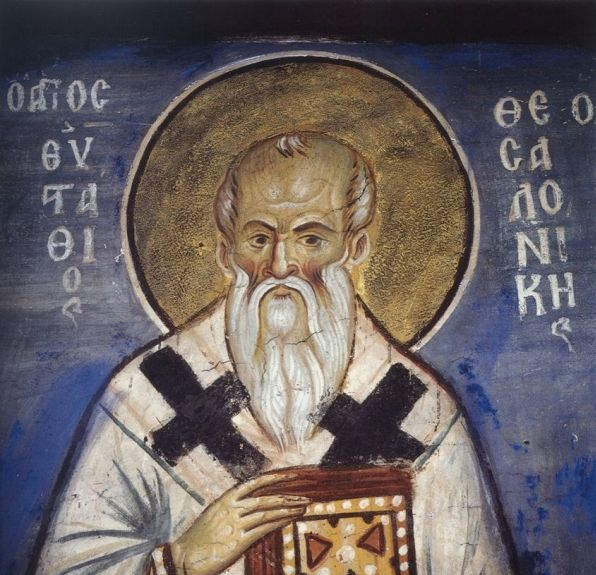

Eustathius of Thessaloniki: detail from a fresco in the Vatopedi Monastery on Mount Athos, Greece, 1312.

Eustathios of Thessaloniki

Eustathios of Thessaloniki was one most of the prominent intellectuals of his time. He was probably born around 1115 in Constantinople, where he received the traditional education in grammar, rhetoric, and philosophy. He entered the ecclesiastical bureaucracy and was also active as a private teacher of grammar and rhetoric. In the course of his career, he was promoted to the prestigious position of ‘master of the rhetoricians’, that is, Professor of Rhetoric in the Patriarchal School and leading orator at the court of Emperor Manuel I Komnenos. Around 1175, he was appointed Archbishop of Thessaloniki, the second city of the empire, a position he would hold until his death around 1195.

Eustathios produced most of his scholarly works during his time in the capital, although he continued to revise and expand them also after he had relocated to Thessaloniki. He wrote, among other things, a commentary on Pindar, of which only the preface survives; a commentary on the didactic poem Description of the Known World by the geographer Dionysius Periegetes (2nd cent. AD); and monumental commentaries on the Iliad and the Odyssey. Like other Byzantine intellectuals, Eustathios authored many other kinds of texts, including letters, sermons, saints’ lives, essays on various topics, and orations celebrating the emperor and his family. In the last part of this article, we will have a look at the most substantial of all his writings, the Commentary of the Iliad.

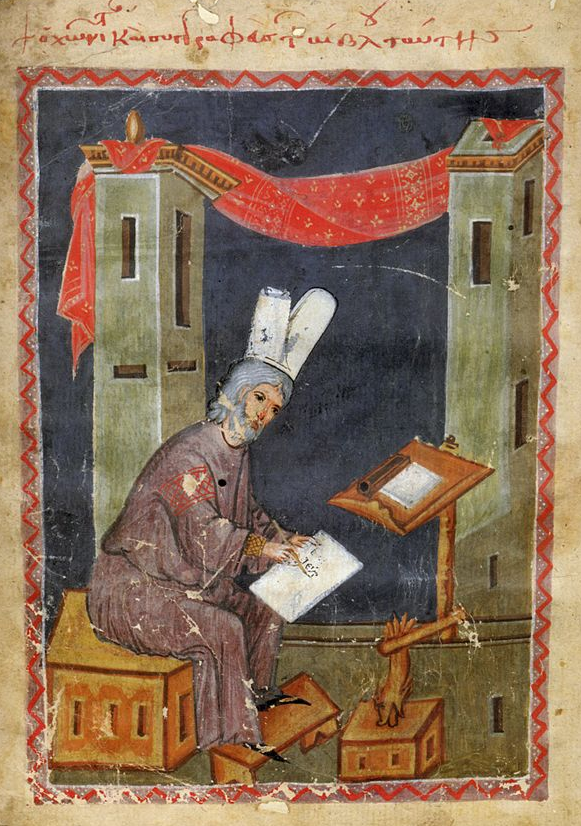

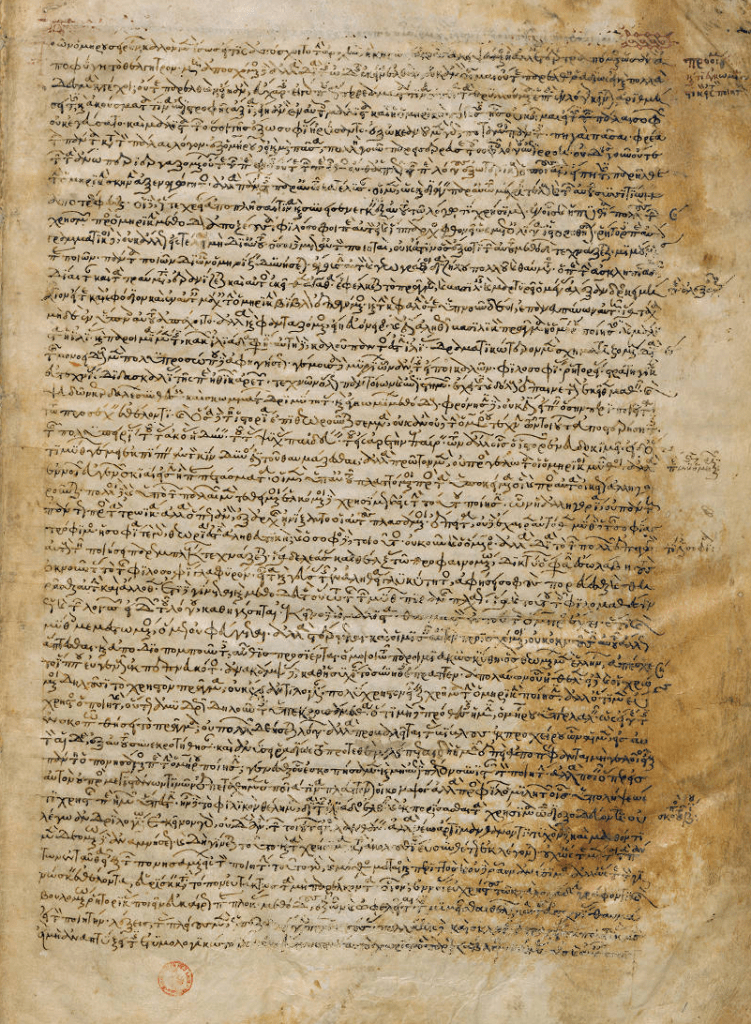

The opening of Eustathius’ autograph copy of his commentary on Homer, 12th cent. (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Italy, MS. Plutei 59.2 f.1r).

Eustathios’ commentary allows us to read the Iliad from beginning to end through Byzantine eyes. It can thus tell us much about the role of Homer in Byzantine education and literary culture. In the work’s preface, Eustathios identifies prose writers as his primary target audience. His commentary, he states, collects all that is useful for practising authors: words to use, lines to quote, rhetorical techniques to apply, etc. Throughout his commentary, Eustathios offers a literary analysis of the Iliad by identifying the rhetorical principles and techniques that allowed the poet to turn his works into veritable masterpieces. Byzantine writers should take Homer’s rhetorical practice as their example if they wish to produce equally compelling works of literature.

The commentary on the Iliad’s first book may serve as an example. Eustathios here explains why Homer started his poem not in the first but in the tenth year of the war: at this point, the events reach their climax and thus provide more material for storytelling. The poet still includes many of the earlier events in his story by means of flashbacks, a technique Eustathios considers typically Homeric. By not following the expected chronological order of the events, the poet prevents the audience from becoming bored: the surprising structure catches the listeners’ attention and makes the narrative more appealing. A less conventional chronology, so Eustathios advises his readers, showcases more clearly an author’s literary skill.

Central medallion of Calliope, the muse of epic poetry, and Homer, from a mosaic found in a Roman villa at Vichten, Luxembourg, AD c.240 (now in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Trier, Germany).

This brief example shows how Eustathios’ rhetorical reading of the Iliad provides Byzantine prose writers with guidelines to follow when composing their own works. These guidelines take the form both of concrete rhetorical techniques and general principles to keep in mind: writers should strive to catch their audience’s attention, for instance by structuring their work in unexpected ways; an oration or discourse should be varied, which a rhetor can achieve by interrupting his main line of argumentation or narration with anecdotes and similes; and a text should demonstrate a writer’s erudition and virtuosity, while simultaneously imparting to the studious audience a wealth of useful information.

Eustathios’ commentary thus tells us much about his ideas on good authorship and good literature. It does not aim only to elucidate the Homeric text for new audiences, but also to redefine Homer’s rhetorical art in terms relevant to the literary world of his time.

The Sack of Byzantium as depicted in Geoffroi de Villehardouin’s La Conquête de Constantinople, c.1330 (Bodleian Library, Oxford, UK, MS. Laud Misc. 587 f.1r).

When the Latin crusaders melted the statue of Helen, they destroyed not just a bronze artefact but the cultural values of Byzantine Constantinople. For the highly-educated Choniates, the Byzantine Empire was inextricably connected with ancient culture as represented, most prominently, by Homer and his Helen. Our 12th-century teachers demonstrate how Homeric poetry was used to teach the Ancient Greek language, to offer guidelines for producing new works of literature, and to impart cultural knowledge. This knowledge carried social and professional importance for anyone belonging to the empire’s elite or seeking rapprochement with the highest circles of the imperial capital. Owing to their central role in Byzantine culture and education, works of valued authors such as Homer, Euripides, and Aristophanes continued to be copied and to survive into the modern day, where they attract a wider readership than ever.

Baukje van den Berg is Associate Professor of Byzantine Studies at the Central European University, Vienna. Her research focuses on Byzantine education and literary thought, as well as the role of ancient literature in Byzantine culture. She is the author of Homer the Rhetorician: Eustathios of Thessalonike on the Composition of the Iliad (Oxford UP, 2022).

Further Reading

Choniates’ History can be read in the translation by H.J. Magoulias, O City of Byzantium, Annals of Niketas Choniates (Wayne State UP, Detroit, MI, 1984). Adam J. Goldwyn and Dimitra Kokkini have translated Tzetzes’ Allegories of the Iliad and Odyssey for Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library (Harvard UP, Cambridge, MA, 2015 and 2019). Eric Cullhed has edited and translated the first two books of Eustathios’ Commentary on the Odyssey, which is available here. Together with S. Douglas Olson, he is currently preparing an edition with translation of the entire commentary (see here).

An overview of Byzantine scholarship (including that of Tzetzes and Eustathius) can be found in F. Pontani, "Scholarship in the Byzantine Empire (529–1453)," in F. Montanari (ed.), History of Ancient Greek Scholarship: From Its Beginnings to the End of the Byzantine Age (Brill, Leiden, 2020) 373–529. For a recent study on Choniates and the destruction of ancient statuary, see F. Spingou, "Classicizing Visions of Constantinople after 1204: Niketas Choniates’ De Signis Revisited," Dumbarton Oaks Papers 76 (2022) 181–220 (available here). Eustathios’ rhetorical reading of the Iliad is the subject of my monograph Homer the Rhetorician: Eustathios of Thessalonike on the Composition of the Iliad (Oxford UP, 2022).

A Dutch version of this article will be published in Hermeneus 96.1 (2024).

https://antigonejournal.com/2024/03/homer-byzantine-eustathios-tzetzes/