Aeschylus - Prometheus Unbound - Rebuilding a Lost Masterpiece

Published by Reblogs - Credits in Posts,

Aeschylus’ Prometheus Unbound: Rebuilding a Lost Masterpiece

Carey Jobe

Today we possess Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus (525/24-456/55 BC) because scholars at the Library of Alexandria chose it as one of seven Aeschylean plays (out of at least 73) to be copied as the canonical selection for libraries and schools.[1]There is intense controversy about whether this play was by Aeschylus or wrongly attributed to him at a later date. For this, readers are referred to Mark Griffith ‘The Authenticity of Prometheus Bound’ (Cambridge UP, 1977) and his commentary on the play (Cambridge UP, 1983, 2nd ed. 2007). Consequently, it was re-copied through the Dark and Middle Ages all over the Byzantine Empire until Renaissance Humanists obtained manuscripts that were transported to Italy and eventually printed.[2]With respect to the issue of text transmission, important resources are Nigel Wilson’s now-classic Scribes and Scholars (Oxford UP, 4th ed., 2014), as well as his books Scholars of Byzantium (Duckworth, London, 1983) and From Byzantium to Italy (Bloomsbury, London, 2016). Aeschylus’ other plays disappeared. Such was the fate of Prometheus Unbound (Promētheus Luomenos in Greek), the sequel to Prometheus Bound. Although not chosen as part of the Aeschylean canon, the Unbound was widely read and quoted in antiquity. As a result, we have enough quotations and other information about this play to form a general idea of how its plot and themes progressed.

Prometheus Unbound carries forward and completes the story of Prometheus begun in Prometheus Bound. This article will translate the surviving Greek and Latin passages of the Unbound and assemble them into the framework of a proposed plot. Prometheus Bound describes the punishment of Prometheus by Zeus following his theft of fire. Bound by Hephaestus to a rock in the Caucasus Mountains, Prometheus is visited, in turn, by the Daughters of Oceanus (the Chorus of the play), then by Ocean himself, Europa, and Hermes, all of whom comment and advise on his plight. Throughout the play, Prometheus remains defiant, alluding to his secret foreknowledge of Zeus’ downfall. As the play concludes, Hermes causes Prometheus to be consumed by a storm for failing to reveal this secret. Prometheus appeals to earth and sky to witness his unjust punishment.

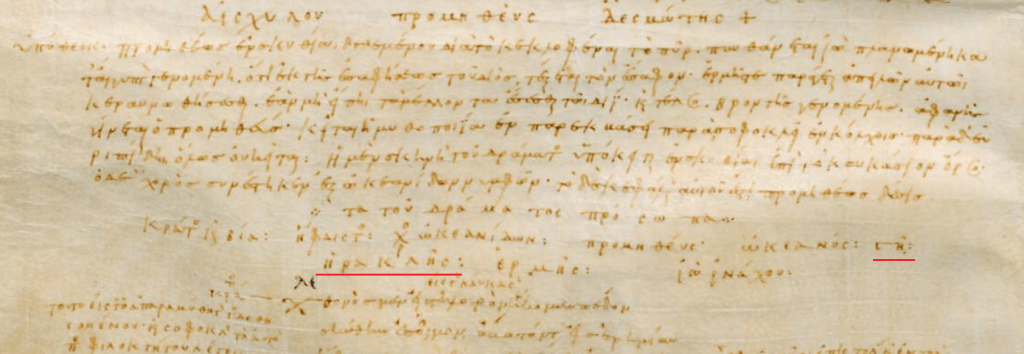

In reconstructing the portions of the Unbound for which no quotations survive, an ancient copyist’s mistake is crucial. The oldest manuscript copy of Prometheus Bound (the 11th-century Medicean manuscript) contains a dramatis personae that includes Gaia and Heracles, although neither appears in that play. We know from ancient sources that Heracles appeared in Unbound, so it is thought that the Medicean textual tradition copied the character list for both plays. This particular error is indispensable for reconstructing Unbound.

At the beginning of Prometheus Unbound, Prometheus remains bound to the rocks of the Caucasus Mountains, where the eagle of Zeus repeatedly consumes his liver, only to be consumed again (in Aeschylus’ version) every third day. The play began with the entrance of the Chorus of Titans. In overthrowing Cronos, Zeus defeated the Titans in a battle known as the ‘Titanomachy’ and condemned them to Tartarus as punishment. In an act of clemency, Zeus has now freed the Titans from imprisonment. They describe their route from Tartarus to Caucasia.

φοινικόπεδόν τ’ Ἐρυθρᾶς ἱερὸν χεῦμα Θα-

λάσσης χαλκοκέραυνόν τε παρ’ Ὠκεανῷ λίμναν †παν-

το† τροφὸν Αἰθιόπων, ἵν’ ὁ παντ{επ}όπτας Ἥλιος αἰεὶˈ

χρῶτ’ ἀθάνατον κάματόν θ’ ἵππων θερμαῖς ὕδατος ˈ

μαλακοῦ προχοαῖς {τ’} ἀναπαύει·

ἥκομεν… τοὺς σοὺς ἄθλους τούσδε, Προ-

μηθεῦ, δεσμοῦ τε πάθος τόδ’ ἐποψόμενοι.

πῇ μὲν δίδυμον χθονὸς Εὐρώπης μέγαν ἠδ’

Ἀσίας τέρμονα Φᾶσιν.[3]The Greek and Latin texts of the fragments of Prometheus Unbound translated in this article were taken from the following volumes of the Loeb Classical Library: Aeschylus Vol. 2 (ed. H. Lloyd-Jones, 1971) 446–53, 497; Cicero, Tusculan Disputations (ed. J.E. King, 1927) 170–2.

… beyond the Red Sea’s depths

that glitter like bronze,

Ethiopia’s sacred river, nourishing all,

and the circling streams of Ocean

where all-seeing Helios daily

bathes his immortal body,

refreshing his weary horse-teams

in gentle upwellings of water…

… by Phasis, rugged border

of Europe and boundless Asia…

we come…

to witness your sufferings, Prometheus,

the piteousness of your bonds.[4]This, and all other translations in the piece, are by the author.

Prometheus then addresses the Titans in a speech translated into Latin by the Roman statesman Cicero in his Tusculan Disputations. The original Greek text is lost. After ages of torture, Prometheus remains defiant, but that defiance is now mixed with suffering:

Titanum suboles, socia nostri sanguinis,

generata Caelo, aspicite religatum asperis

vinctumque saxis, navem ut horrisono freto

noctem paventes timidi adnectunt navitae.

Saturnius me sic infixit Juppiter,

Iovisque numen Mulciberi ascivit manus.

hos ille cuneos fabrica crudeli inserens

perrupit artus: qua miser sollertia

transverberatus castrum hoc Furiarum incolo.

iam tertio me quoque funesto die

tristi advolatu aduncis lacerans unguibus

Iovis satelles pastu delaniat fero.

tum iecore opimo farta et satiata adfatim,

clangorem fundit vastem et sublime advolans

pinnata cauda nostrum adulat sanguinem.

cum vero adesum inflate renovatum est iecur,

tum rursus taetros avida se ad pastus refert.

sic hanc custodem maesti cruciatus alo

quae me perenni vivum foedat miseria.

namque, ut videtis, vinclis constrictus Iovis

arcere nequeo diram volucrem a pectore.

sic me ipse viduus pestes excipio anxias,

amore mortis terminum anquirens mali.

sed longe a leto numine aspellor Iovis.

atque haec vetusta saeclis glomerata horridis

luctifica clades nostro infixa est corpori,

e quo liquitae solis ardore excidunt

guttae, quae saxa adsidue instillant Caucasi.

(Cicero, Tusculan Disputations 2.10.23–5)

Race of Titans, kinsmen of my blood,

Heaven’s progeny, behold me shackled, bound

to harsh rocks, like a ship moored fast by sailors

timid and fearful of night’s thundering sea.

Zeus, Cronos’ vengeful son, transfixed me thus;

Hephaistos’ craft then hardened the god’s rage.

With cruel hands he split my limbs with bolts

that, by his handiwork, I miserably

inhabit this bleak stronghold of the Furies.

Every third dismal day, with dreadful swoop,

Zeus’ minister, an eagle, with hooked talons

slashes my liver for its gruesome feast

until, glutted and stuffed on my fat vitals,

it utters a horrendous scream and soars

aloft, its feathered tail fanning my blood.

Then when my liver swells, regenerating,

it swoops back hungry for fresh butchery.

This guardian of my sorrows, whom I nourish,

consumes me living with unending pain,

for, as you see, imprisoned in Zeus’ chains

I cannot hurl this monster from my breast.

Deprived of any aid, I must endure

pernicious tortures, yearning for the death

that ends my woes, yet by the wrath of Zeus,

despite my wish, I keep this bed of anguish.

These ancient, grievous torments, magnified

through horrid ages, fasten on my body

from which drops, melted by the torrid sun,

run ceaselessly down the rocks of Caucasus.

Following this speech came what was probably the central episode of the play. Gaia, the Earth Goddess and mother of Prometheus, arrives to console and advise her son. No passages of their dialogue survive, but Prometheus relates in Bound that Gaia often told him the course of future events (ll.211–13). We can imagine she did so here, too. But she also worked to shape events. Prometheus also says in Bound that during the Titanomachy Gaia and Prometheus shifted their allegiance to Zeus, a switch crucial in ensuring Zeus’ triumph (218–20). Given Gaia’s active role in the Zeus-Prometheus alliance, she would probably have offered Prometheus advice on how to mend this rift and end his captivity. She might have explained that an ordered cosmos is guided by principles of justice – brute power alone is unsustainable. Realizing this, Zeus softened his harshness with mercy. Hence, Prometheus’ defiance serves no purpose. The time for reconciliation has come.

After Gaia’s departure, the play’s events move quickly. Heracles arrives at Prometheus’ rock on his trek northward to steal the apples of the Hesperides. He asks Prometheus for advice on the route he must take and the dangers he will face. Prometheus’ account of Heracles’ travels contained colorful descriptions of the peoples and places he will meet on his journey.

As Heracles journeys northward, Prometheus warns, he must face the North Winds:

εὐθεῖαν ἕρπε τήνδε· καὶ πρώτιστα μὲν

βορεάδας ἥξεις πρὸς πνοάς, ἵν’ εὐλαβοῦ

βρόμον καταιγίζοντα, μή σ’ ἀναρπάσῃ

δυσχειμέρῳ πέμφιγι <συ>στρέψας ἄφνω…

Take this straight road, where you will first encounter

the gales of Boreas – there stay vigilant

against the howling blizzards that can swiftly

snatch men away like leaves in freezing whirlwinds…

On his homeward journey following the theft of the apples, Heracles will encounter the Ligures, a historically-documented people who inhabited the region of Italy known today as Liguria:

ἥξεις δὲ Λιγύων εἰς ἀτάρβητον στρατόν,

ἔνθ’ οὐ μάχης, σάφ’ οἶδα, καὶ θ<ο>ῦρός περ ὢν

μέμψῃ· πέπρωται γάρ σε καὶ βέλη λιπεῖν

ἐνταῦθ’, ἑλέσθαι δ’ οὔ τιν’ ἐκ γαίας λίθον

ἕξεις, ἐπεὶ πᾶς χῶρός ἐστι μαλθακός.

ἰδὼν δ’ ἀμηχανοῦντά σ’ ὁ Ζεὺς οἰκτιρεῖ,

νεφέλην δ’ ὑποσχὼν νιφάδι γογγύλων πετρῶν

ὑπόσκιον θήσει χθόν’, οἷς ἔπειτα σὺ

βαλὼν διώσῃ ῥᾳδίως Λίγυν στρατόν.

…You then confront fearless Ligurian warriors,

where, I foresee, your courage will desert you,

your arrows prove too few, and where you cannot

even throw stones, for the whole plain is smooth.

Yet, pitying you, the Father will spread clouds

above the land that drop a blanket of stones.

Hurl these, and you will rout the Ligurian hordes.

Heracles then meets the Gabioi ("Gabians"), presumably a reference to the Gabii, a tribe that in Roman times lived in central Italy. Their life resembles a remnant of the Golden Age:

ἔπειτα δ’ ἥξεις δῆμον ἐνδικώτατον

<βροτῶν> ἁπάντων καὶ φιλοξενώτατον,

Γαβίους, ἵν’ οὔτ’ ἄροτρον οὔτε γατόμος

τέμνει δίκελλ’ ἄρουραν, ἀλλ’ αὐτοσπόροι

γύαι φέρουσι βίοτον ἄφθονον βροτοῖς.

Thereafter you will meet a folk more righteous

and more hospitable than any other,

the Gabians, a people who require

no plow or spade, no tool that breaks the earth,

to raise crops, whose fields, self-sown without toil,

ripen in bountiful harvests for mankind.

In gratitude for this advice, Heracles agrees to slay the eagle, the dramatic high point in what is primarily a speech-focused play. He puts an arrow on his bow, praying for divine aid:

Ἀγρεὺς δ’ Ἀπόλλων ὀρθὸν ἰθύνοι βέλος.

Archer Apollo, guide my arrow straight!

Heracles’ arrow slays the eagle, and he then unshackles Prometheus. After ages of bondage, Prometheus is freed – and he does not fail to note the irony that a son of Zeus has freed him:

ἐχθροῦ πατρός μοι, τοῦτο, φίλτατον τέκνον.

My fiercest foe has sired this dearest son!

The play is nearing its conclusion. No quotations exist, but the 3rd-century scholar Athenaeus of Naucratis relates that in Unbound Prometheus agreed to wear a flower garland as atonement for the theft of fire (Deipnosophistae 15.16). Aeschylus’ trilogies of tragedes seem often to have ended by linking mythological events to a custom or ritual practised in Athens. Athenaeus’ statement suggests that the ending of Unbound described the initiation of the annual festival in Athens honoring Prometheus, during which participants wore a garland to commemorate Prometheus’ bonds [5]See further Mark Griffith. Aeschylus Prometheus Bound: Text and Commentary (Cambridge UP, 1983) 281–3. Cambridge, 1983.

Although no ancient sources describe the conclusion of Unbound, the proclamation of a festival would probably have been part of a speech by an emissary of Zeus announcing Prometheus’ pardon. If the Medicean manuscript really does list the characters who appeared in Unbound, Hermes is quite simply the only possibility, reprising the role he played at the end of Bound. His reappearance, too, would be a dramatically effective way to bring the two plays full circle. Hermes would now appear to announce that Prometheus is pardoned, that Heracles killed the eagle on orders of Zeus, and that Prometheus’ punishment is reduced to wearing a flower garland, to be worn during an annual festival in Athens. Prometheus, in a gesture of amity, would now warn Zeus to abandon his desire for the nymph Thetis, as she is destined to give birth to a child greater than his father. Prometheus urges Zeus to marry Thetis to the mortal Peleus, and prophesies the glory of their future child, Achilles. The Titans sing a celebratory closing hymn to conclude the play.

Prometheus Bound reads like a middle play in its trilogy: the action is already afoot, and the ending is inconclusive. As Aeschylus normally wrote trilogies, a prelude seems to be called for, yet we have no conclusive evidence about a third play. A single line attributed to a play called Prometheus the Fire-Bringer (Purphoros) might in fact refer to Prometheus the Fire-Kindler (Purkaeos), the satyr play appended to the Persians trilogy in 472 BC. My guess is that both Bound and Unbound were left complete when Aeschylus died in Gela, Sicily, in 456 or 455 BC, and that he simply did not live long enough to write a third play. As we are likely never to know the answer, we must surely consider Bound and Unbound as a "duology" rather than a trilogy.

Beneath their surface resemblances, the two plays head in different moral directions. Bound was about the shattering of the cosmic order, a lone individual’s unequal struggle against tyrannical force, armed only with knowledge. The conclusion of the play leaves the audience in a world where brute force has the upper hand. The sequel play seems to resolve these dissonances. At the conclusion of Prometheus Unbound, we understand that justice is built into the fabric of the cosmos. Zeus’ power and Prometheus’ foresight were intended to form a unity. This lesson was highly relevant for 5th-century Athens on the brink of the Peloponnesian War. However, the theme of justice through the harmony of opposing forces illuminated in Prometheus Unbound remains pertinent for the discords of our own age, as in every age.

That great idea is underscored in a final quotation attributed to the Unbound, words probably sung by the chorus in the play’s celebratory conclusion:

ὅπου γὰρ ἰσχὺς συζυγοῦσι καὶ δίκη,

ποία ξυνωρὶς τῶνδε καρτερωτέρα;

When Strength links arms with Justice,

what mightier pair than this?[6]This is an abridged version of the article appearing in the latest issue of New Lyre Magazine.

Carey Jobe is a retired attorney and judge. Prior to beginning his legal career, he was a student of Classical Literature and Latin Language. His Latin translations have appeared in Classical Outlook, the journal of The American Classical Society. He is also a widely published poet whose work regularly appears in numerous literary journals. He lives and writes near Tallahassee, Florida.

Notes

| ⇧1 | There is intense controversy about whether this play was by Aeschylus or wrongly attributed to him at a later date. For this, readers are referred to Mark Griffith ‘The Authenticity of Prometheus Bound’ (Cambridge UP, 1977) and his commentary on the play (Cambridge UP, 1983, 2nd ed. 2007). |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | With respect to the issue of text transmission, important resources are Nigel Wilson’s now-classic Scribes and Scholars (Oxford UP, 4th ed., 2014), as well as his books Scholars of Byzantium (Duckworth, London, 1983) and From Byzantium to Italy (Bloomsbury, London, 2016). |

| ⇧3 | The Greek and Latin texts of the fragments of Prometheus Unbound translated in this article were taken from the following volumes of the Loeb Classical Library: Aeschylus Vol. 2 (ed. H. Lloyd-Jones, 1971) 446–53, 497; Cicero, Tusculan Disputations (ed. J.E. King, 1927) 170–2. |

| ⇧4 | This, and all other translations in the piece, are by the author. |

| ⇧5 | See further Mark Griffith. Aeschylus Prometheus Bound: Text and Commentary (Cambridge UP, 1983) 281–3. Cambridge, 1983. |

| ⇧6 | This is an abridged version of the article appearing in the latest issue of New Lyre Magazine. |

Tags: Greek