Handy Mnemonics: The Five-Fingered Memory Machine – The Public Domain Review

Published by Reblogs - Credits in Posts,

Before humans stored memories as zeroes and ones, we turned to digital devices of another kind — preserving knowledge on the surface of fingers and palms. Kensy Cooperrider leads us through a millennium of "hand mnemonics" and the variety of techniques practised by Buddhist monks, Latin linguists, and Renaissance musicians for remembering what might otherwise elude the mind.

Published

April 21, 2022

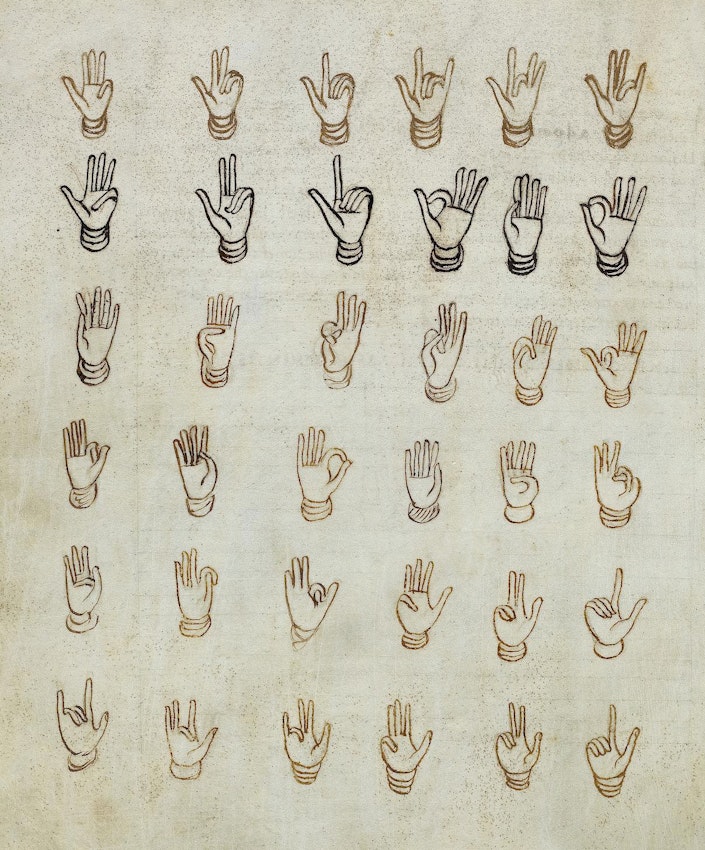

Drawing on paper from Mogao Caves, reproduced in the fourth volume of Aurel Stein’s Serindia: Detailed Report of Explorations in Central Asia and Westernmost China (1921) — Source.

No one knows who made the drawing. Likely the work of an eighth-century monk, perhaps a member of an esoteric Buddhist cult traveling the Silk Road, it long sat forgotten in a walled-off library in China’s Mogao Caves. When the library was uncovered in 1900, the drawing — lifted from a trove of religious manuscripts — had aged well. Its subject is timeless: a pair of human hands.

The hands are disembodied, perched on lotus petals, palms facing the viewer. Their fingers — vigorous and elegant — are annotated with Chinese characters: the lowest tier of characters, on the tips, names each digit; above that, a second row gives the five Buddhist elements: space, wind, fire, water, and earth; and a final tier, floating upwards as if on kite strings, lists the ten virtues — among them meditation, effort, charity, wisdom, and patience. The drawing illustrates a mnemonic system, a way of projecting knowledge onto the hands so it can be studied, memorized, and stashed in a pocket.

Around the same time this mnemonic was made, another monk — in a Northumbrian monastery, halfway around the world — was developing a different system of manual knowledge. His name we do know: Bede. In 725, he published a treatise, The Reckoning of Time, in which — alongside discussions of shadows, moonlight, and the solstices — he laid out a method for determining when Easter would fall on any given year.

"Loquela digitorum" (finger reckoning) after Bede, from an early 9th-century manuscript — Source.

To find the date of Easter — which falls after the Northern Hemisphere’s spring equinox, on the Sunday immediately following the first full moon — one needs to reckon with planetary rhythms, which Bede mapped across his hands. The five fingers, he observed, contain fourteen joints, plus five nails — nineteen landmarks in all. This number tracks the metonic cycle: how many years it takes for the moon to return to the same phase on the same calendrical day. The joints of both hands taken together, minus the nails, gives you twenty-eight landmarks: the approximate length in years of a full solar cycle. In this way, Bede noted, the hands can "readily hold the cycles of both planets".

These two systems — perhaps the earliest examples of manual mnemonics — come down to us only in outline. And yet we have little trouble recognizing their appeal. They seem to spring from an impulse that transcends time and place, a deeply human drive to reach for props to help us reason and remember. "When thought overwhelms the mind", the psychologist Barbara Tversky has written, "the mind puts it into the world".

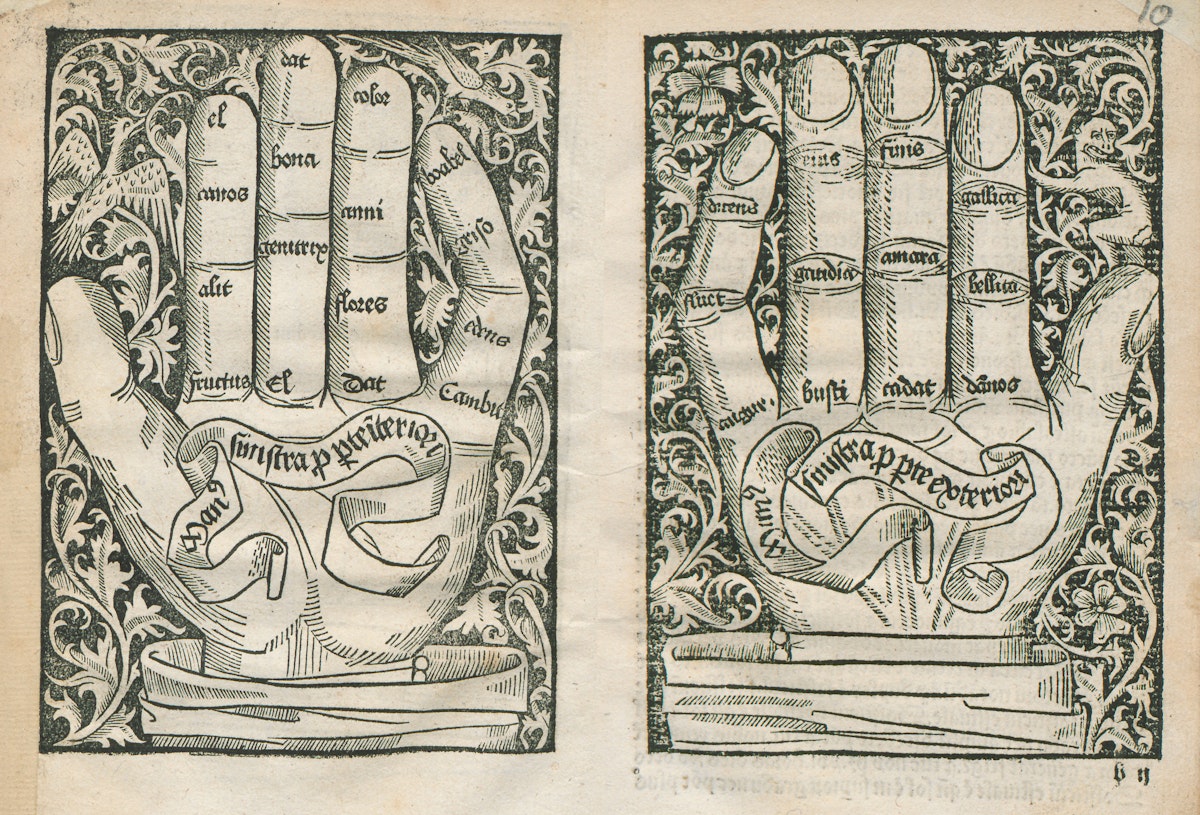

Woodcut illustrations from Anianus’ Compotus cum commento (ca. 1492), an adaptation of Bede’s computus system — Source.

In the beginning, the hand was just a hand — or so we can imagine. It was a workaday organ, albeit a versatile one: a tool for grasping, holding, throwing, and hefting. Then, at some point, after millions of years, it took on other duties. It became an instrument of mental, not just menial, labor. As a species, our systems of understanding, belief, and myth had grown more elaborate, more cognitively overwhelming. And so we started to put those systems out into the world: to tally, track, and record by carving notches into bone, tying knots in string, spreading pigment on cave walls, and aligning rocks with celestial bodies. Hands abetted these early mental labors, of course, but they would later become more than mere accessories. Beginning roughly twelve hundred years ago, we started using the hand itself as a portable repository of knowledge, a place to store whatever tended to slip our mental grasp. The topography of the palm and fingers became invisibly inscribed with information of all kinds — tenets and dates, names and sounds. The hand proved versatile in a new way, as an all-purpose memory machine.

The arts of memory are well known, but the role of the hand in these arts is often overlooked. In the twentieth century, beginning with the pioneering work of Frances Yates, Western scholars started to piece together a rich tradition of mnemonic practices that originated in antiquity and later took hold in Europe.

The two traditions do have important differences. Memory palaces exist solely in the imagination; hand mnemonics exist half in the mind and half in the flesh. Another difference lies in their intended use. Memory palaces are idiosyncratic in nature, tailored to the quirks of personal experience and association, and used for private purposes; they are very much the province of an individual. Hand mnemonics, by contrast, are the province of a community, a tool for collective understanding. They offer a way of fixing and transmitting a shared system of knowledge. They serve private purposes, certainly — such as contemplation, in the case of the Mogao mnemonic, or calculation, in the case of Bede’s computus. But they also have powerful social functions in teaching, ritual, and communication.

Hand-colored woodcut, titled The Hand as the Mirror of Salvation, 1466 — Source.

The richness of this overlooked tradition is glimpsed through its ubiquity. In medieval Europe, Christian hand mnemonics were commonplace. Several echo the Mogao system in appending key teachings to manual loci. A 1466 woodcut from Germany, titled The Hand as the Mirror of Salvation, assigns a different spiritual stage to each finger: God’s will to the thumb; examination to the index; repentance goes on the middle; confession is pinned to the ring; and the pinkie gets satisfaction.

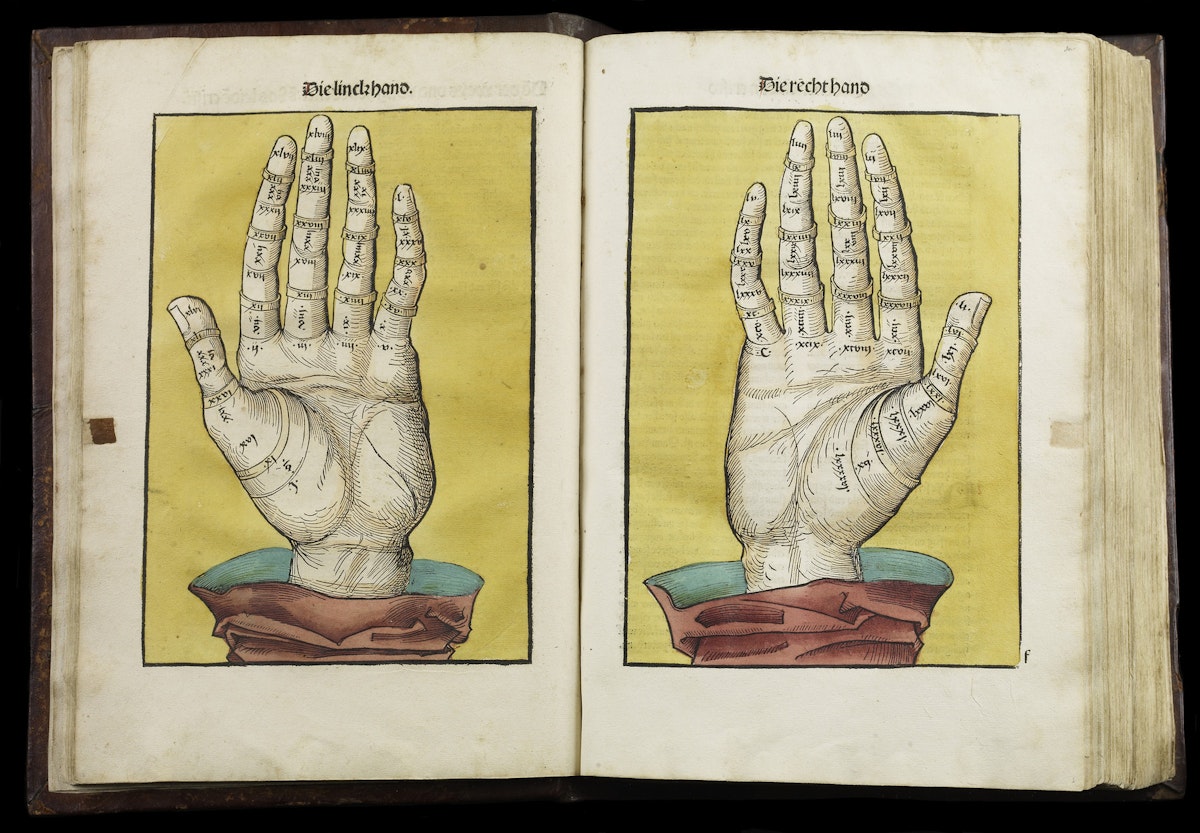

Ink and paint image from Stephan Fridolin’s Schatzbehalter der wahren Reichtumer des Heils (Treasury of the true riches of salvation), published in Nuremberg by Anton Koberger in 1491. Here the hands contain numbers that correspond to meditations in the book, creating a table of contents — Source.

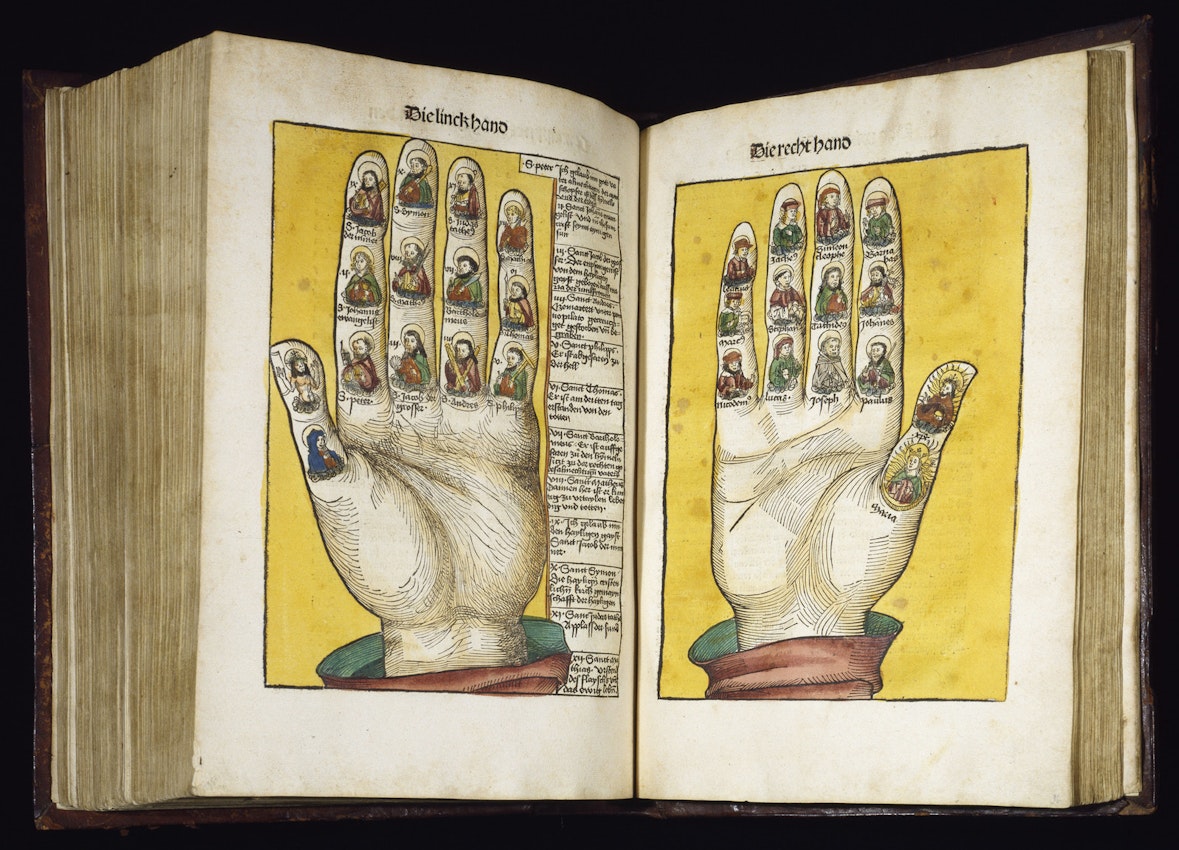

Ink and paint image from Stephan Fridolin’s Schatzbehalter der wahren Reichtumer des Heils (Treasury of the true riches of salvation), published in Nuremberg by Anton Koberger in 1491. Here the hands contain busts of apostles, saints, Mary, and Christ — Source.

In different times and places, hands also furnished mnemonic maps of sound. The so-called "Guidonian hand" owes its name to the eleventh-century Italian music teacher and scholar, Guido d'Arezzo. Arranging the different pitches in a scale onto the joints, he developed this technique to help students learn "unheard melody most easily and correctly".

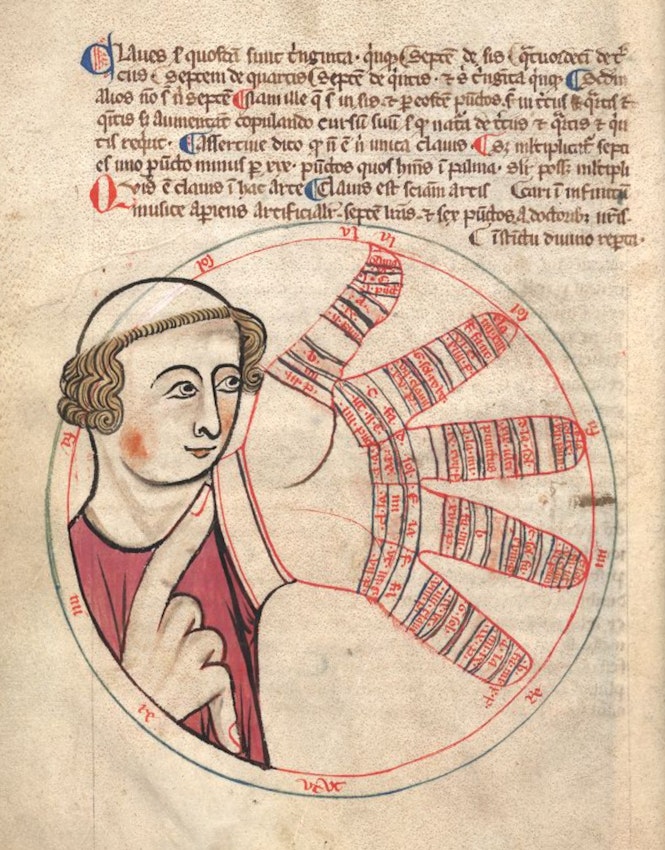

16th-century diagram from the manuscript of an unknown author depicting musical notes scored across a hand in the method attributed to Guido d'Arezzo — Source.

Manuscript illustration of a "Guidonian hand", ca. 1274. "Note how the solmization sequence ut-re-mi-fa-sol-la appears both on the enclosing circle and on the hand itself" — Source.

Other thinkers in Europe — perhaps inspired by Guido — developed systems for learning the sounds of language. In the 1400s, the writer John Holt devised a hand-based technique for remembering the declensions of Latin, and, in 1511, the German scholar Thomas Murner proposed a hand mnemonic for parsing German speech.

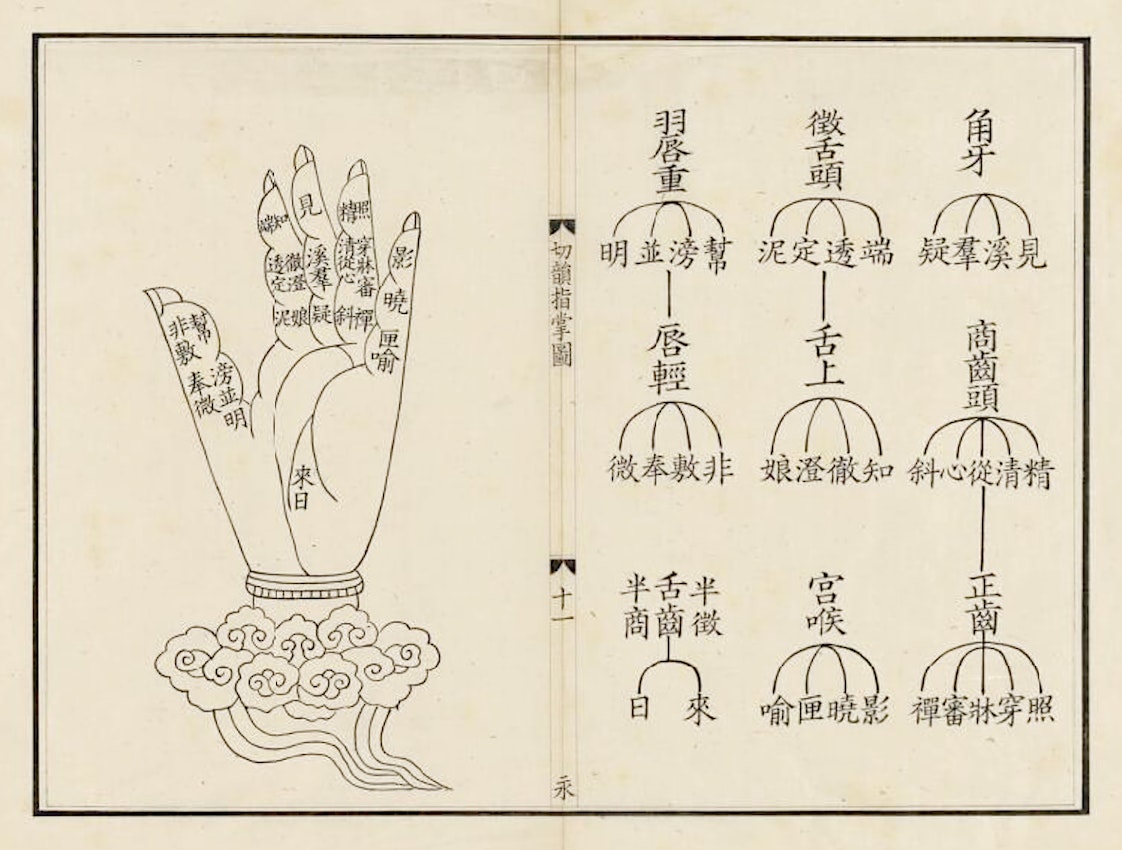

Illustration of a "rime table", from a 19th-century version of Sima Guang’s Qie yun zhi zhang tu (originally published ca. 1050) — Source.

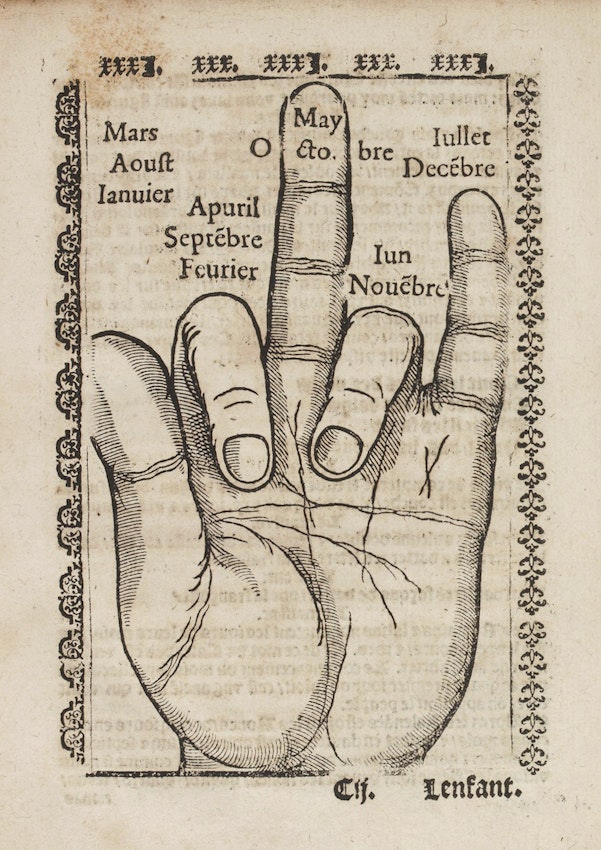

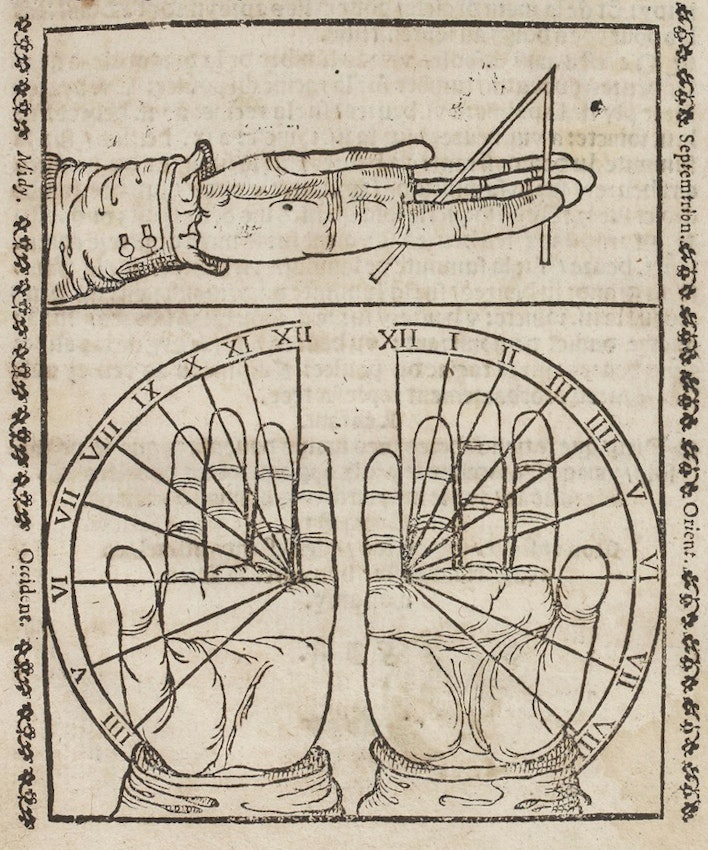

In Europe, a number of mnemonics, sprung from the rootstock of Bede’s system, used the hand to reckon time. A remarkable example comes from a 1582 volume of practical astronomy by Jehan Tabourot, a French polymath best known for his work on dance, who published under an anagrammatic pen name, Thoinot Arbeau. The volume is a slim sixty-one pages, but eleven of those pages include images of hands — presented in various configurations and layered over with different kinds of data. Among these is a mnemonic for keeping track of a notorious calendrical quirk: the alternation of long and short months. The image shows a left hand; the thumb, middle, and pinkie fingers are extended, while the index and ring fingers are curled back toward the palm. The system begins with March, pegged to the extended thumb (31 days); then proceeds rightward to April on the curled-in index finger (30 days); then to May on the extended middle finger (31 days); and so on. It continues by traversing the five fingers twice, ending with January (31 days) on the thumb and February (28 days) on the index.

Illustration from Thoinot Arbeau’s 1582 volume of practical astronomy, demonstrating the use of a "hand calendar" — Source.

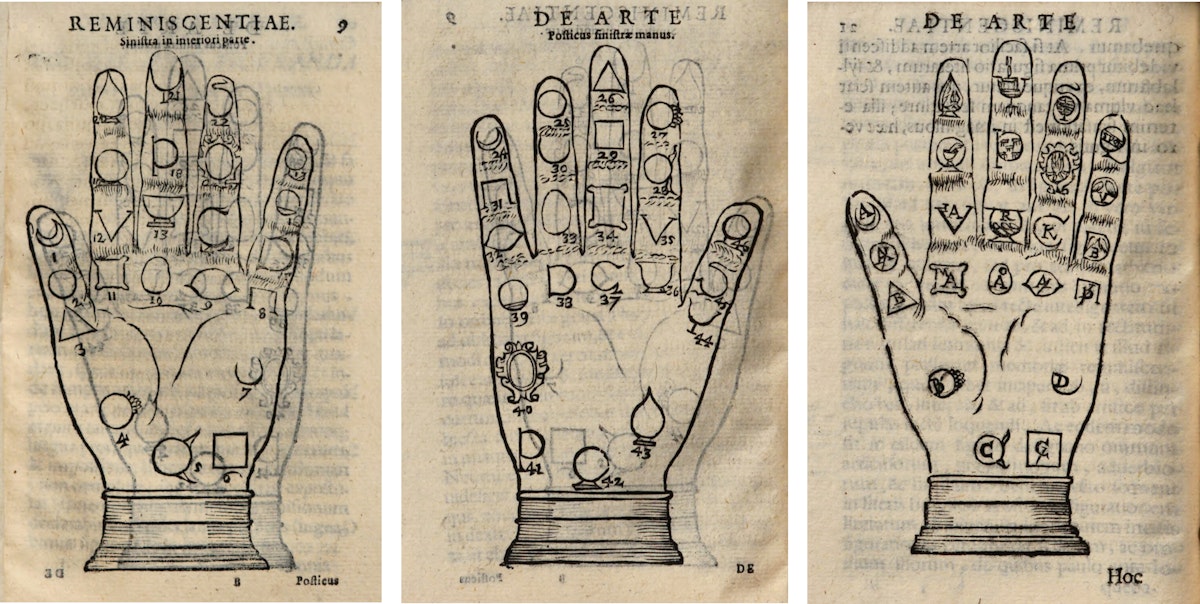

One of the most ambitious of all hand mnemonics was not tailored for time or sound or any one type of information. It was presented by Girolamo Marafioti of Calabria in a 1602 treatise on the arts of memory.

Hands from Girolamo Marafioti’s 17th-century treatise on the art of memory, De Arte Reminiscentiae, demonstrating the use of loci — Source.

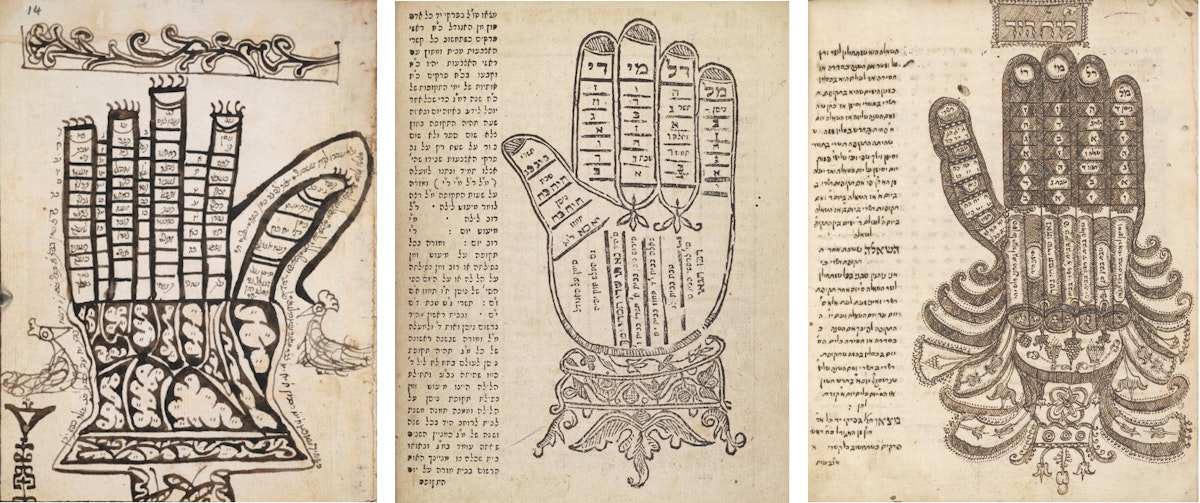

A global survey of hand-mnemonics includes Jewish hand-calendars that resemble Bede’s computus

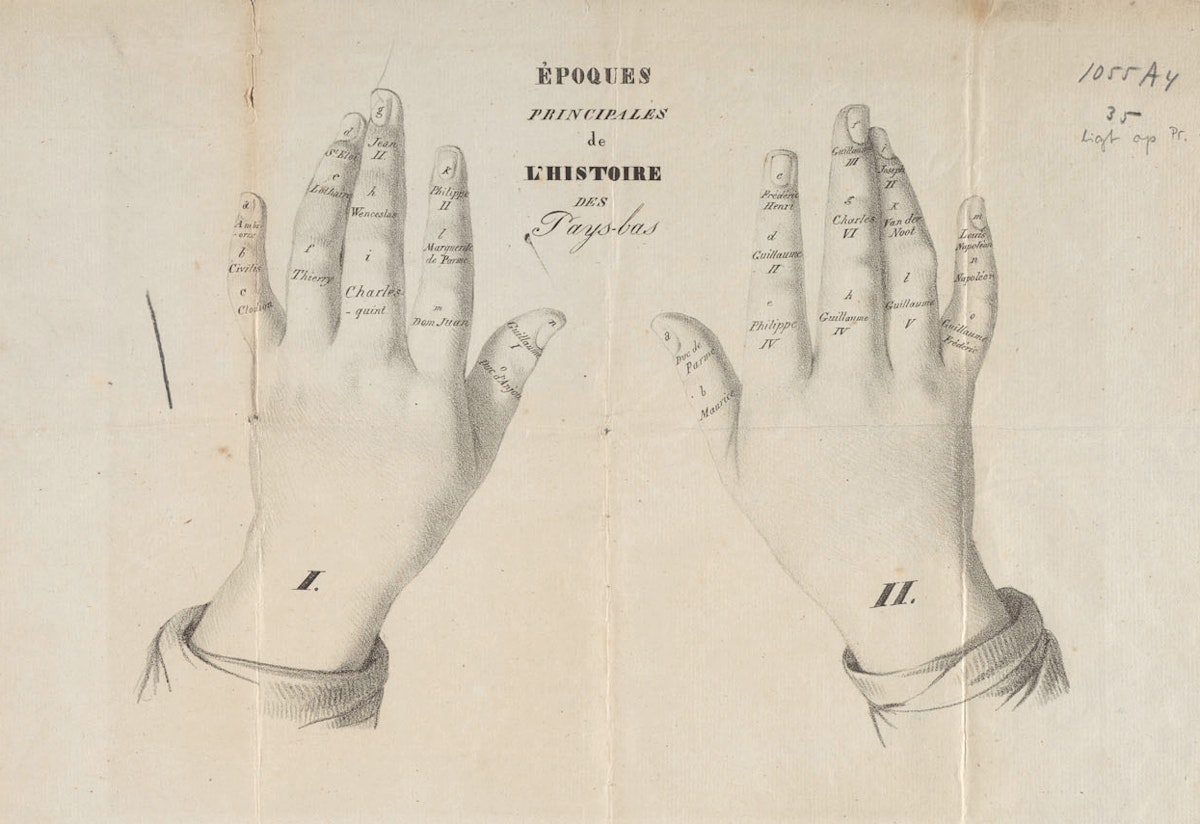

An 1815 guide by H. Somerhausen for remembering significant epochs from Dutch history — Source.

Illustration from Thoinot Arbeau’s 1582 volume of practical astronomy, demonstrating how to convert the hands into a sundial — Source.

Spending time amid this rich tradition, questions arise. First, what makes the hand so popular as a mnemonic prop? A large part of the answer, surely, involves portability. The hands are always, well, ready to hand. Another part is familiarity. Though popular wisdom stresses how well we know the back of our hand, the palm is hardly terra incognita. A further advantage stems from how hand mnemonics offer both visual and kinesthetic routes to memory: they are both seen and felt.

But why did hand mnemonics emerge when they did? What niche did they fill? The examples considered here suggest the tradition flourished in a period when literate and oral cultures coexisted, a time when some — the scholarly elites — were developing complex systems of knowledge in monasteries and universities, while others — the broader public — were trying to master those systems and use them in everyday life. Hand mnemonics may have been perfectly positioned to shuttle between these two cultures. They bridged the voice and the pen, offering, to the trained imagination, a kind of living inscription.

The thorniness here is that it’s difficult to say with confidence when exactly hand mnemonics flourished. We could assume they got their start around 1200 years ago, based on the earliest surviving examples. But it’s quite plausible that similar techniques had been in use for centuries or longer. Perhaps no earlier evidence survives because hand mnemonics were so widely used, so mundane, that no one thought to mention them. Recall that Bede didn’t bother to illustrate his famed system. Neither did Guido.

It's also hard to determine when and why hand mnemonics faded out — that is, if they have. Many continue to remember the alternation of long and short months by projecting them onto the knuckles, an update of Tabourot’s system.

Kensy Cooperrider is a cognitive scientist, writer, teacher, and podcaster. He earned a PhD in Cognitive Science from the University of California — San Diego in 2011. His work explores the intersections of language, culture, body, and mind, and has included forays into finger names, Darwin’s metaphors, pointing gestures, time concepts, the history of measurement, and the evolution of language. Kensy’s writing has appeared in Aeon, Atlas Obscura, and Nautilus, among other places. He also hosts Many Minds, a podcast about our world’s diverse varieties of mind, within and beyond our species.

Related Essays

Reading Like a Roman: Vergilius Vaticanus and the Puzzle of Ancient Book Culture

By Alex Tadel

How did Virgil’s words survive into the present? And how were they once read, during his own life and the succeeding centuries? Alex Tadel explores Graeco-Roman reading culture through one of its best-preserved and most lavishly-illustrated artefacts. more

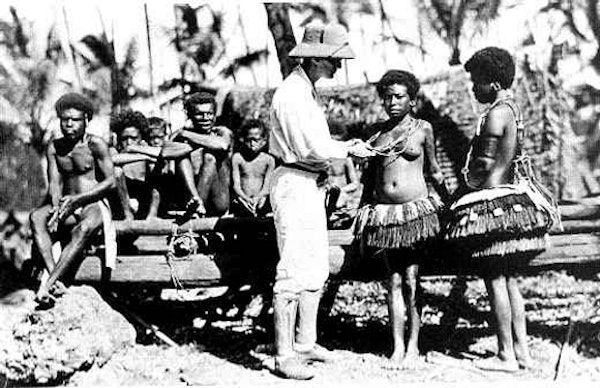

Writing his Life through the Other: The Anthropology of Malinowski

Last year saw the works of Bronislaw Malinowski - father of modern anthropology - enter the public domain in many countries around the world. Michael W. Young explores the personal crisis plaguing the Polish-born anthropologist at the end of his first major stint of ethnographic immersion in the Trobriand Islands, a period of self-doubt glimpsed through entries in his diary - the most infamous, most nakedly honest document in the annals of social anthropology. more

When Chocolate was Medicine: Colmenero, Wadsworth, and Dufour

Chocolate has not always been the common confectionary we experience today. When it first arrived from the Americas into Europe in the 17th century it was a rare and mysterious substance, thought more of as a drug than as a food. Christine Jones traces the history and literature of its reception. more

Tribal Life in Old Lyme: Canada’s Colorblind Chronicler and his Connecticut Exile

Abigail Walthausen explores the life and work of Arthur Heming, the Canadian painter who — having been diagnosed with colourblindness as a child — worked for most of his life in a distinctive palette of black, yellow, and white. more

"O Uommibatto": How the Pre-Raphaelites Became Obsessed with the Wombat

Angus Trumble on Dante Gabriel Rossetti and company's curious but longstanding fixation with the furry oddity that is the wombat — that "most beautiful of God's creatures" which found its way into their poems, their art, and even, for a brief while, their homes. more

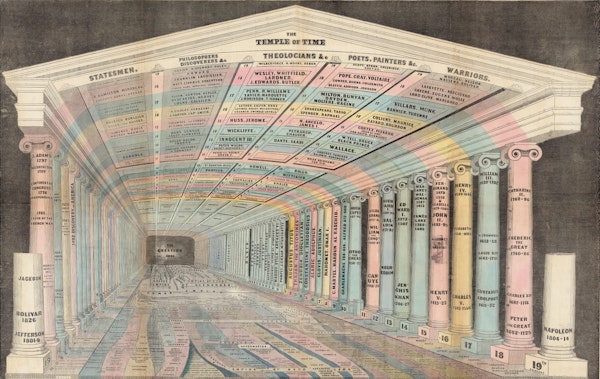

In the 21st-century, infographics are everywhere. In the classroom, in the newspaper, in government reports, these concise visual representations of complicated information have changed the way we imagine our world. Susan Schulten explores the pioneering work of Emma Willard (1787–1870), a leading feminist educator whose innovative maps of time laid the groundwork for the charts and graphics of today. more

Lewis Carroll and The Hunting of the Snark

In 1876 Lewis Carroll published by far his longest poem - a fantastical epic tale recounting the adventures of a bizarre troupe of nine tradesmen and a beaver. Carrollian scholar, Edward Wakeling, introduces The Hunting of the Snark. more

Photographing the Tulsa Massacre of 1921

On the evening of May 31, 1921, several thousand white citizens and authorities began to violently attack the prosperous Black community of Greenwood in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Karlos K. Hill investigates the disturbing photographic legacy of this massacre and the resilience of Black Wall Street’s residents. more

If You Liked This…

Prints for Your Walls

Explore our selection of fine art prints, all custom made to the highest standards, framed or unframed, and shipped to your door.

The majority of the digital copies featured are in the public domain or under an open license all over the world, however, some works may not be so in all jurisdictions. On each Collections post we’ve done our best to indicate which rights we think apply, so please do check and look into more detail where necessary, before reusing. Unless otherwise stated, our essays are published under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 license. Strong Freedom in the Zone.

The Public Domain Review is registered in the UK as a Community Interest Company (#11386184), a category of company which exists primarily to benefit a community or with a view to pursuing a social purpose, with all profits having to be used for this purpose.